When facing with dampness problems, the most common practical questions being asked are:

- What dampness problems my building has?

- How can I fix them?

Diagnosing Dampness Problems - By Building Area

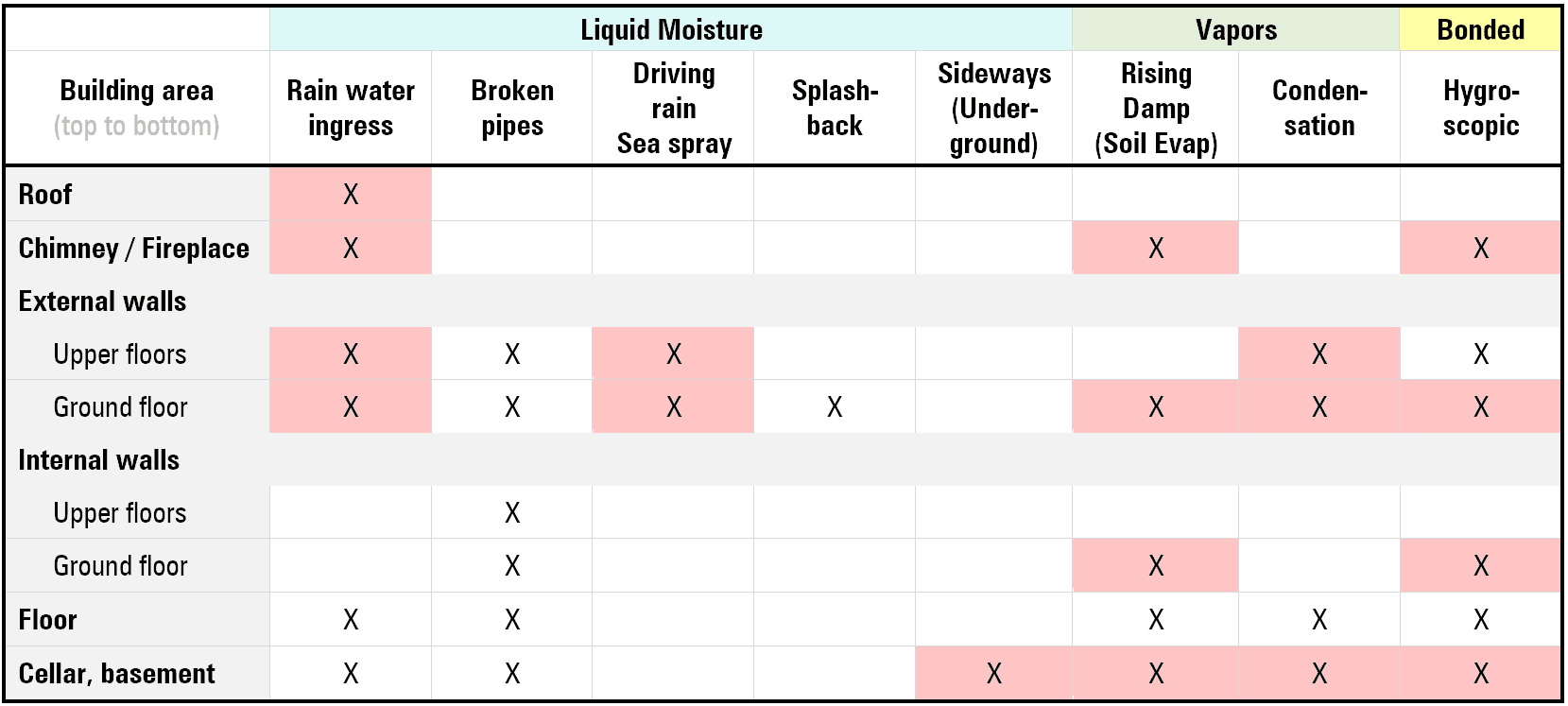

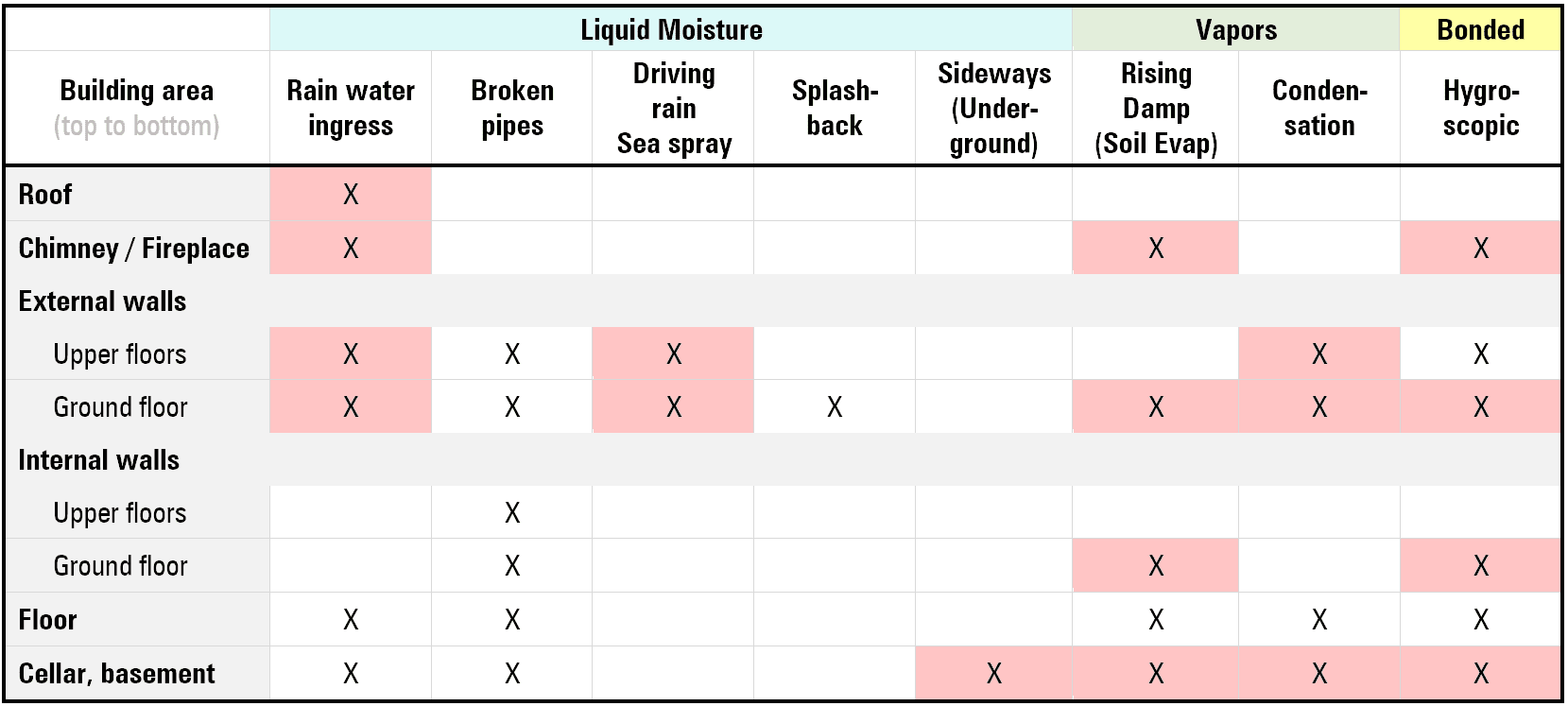

Although dampness in old buildings is a complex and comprehensive topic, we have attempted to cut through the fog and simplify it by summarizing most common problems (from roof to cellar) in the chart below. Common or most likely problems for each building area are highlighted in red.

Most common dampness problems affecting old buildings

Here is a short explanation for each area:

Roofs

Dampness problems in roof areas are mainly about rainwater ingress, water finding its way into the building, causing various leaks.

Such problems mostly affect the upper part of the walls, being more pronounced near the top. Dampness patches have well-defined sharp edges as a result of the abundantly incoming liquid moisture.

Chimneys / Fireplaces

Most common dampness problems in chimney / fireplace areas are the following:

- Leaks: rainwater finds its way down the chimney breast as a result of non-existent or missing chimney caps, flashing or pointing problems. In these cases water staining is often visible inside the chimney.

- Rising damp: old chimneys often have a support function, supporting or re-enforcing wall areas. Just like any other wall section resting on the ground, the base of the chimneys – often consisting of thick, large-volume masonry – are often subject to significant rising damp.

- Hygroscopic (chemically bound, salts-related) moisture: fireplace areas can contain significant amounts of salts, that can originate from 2 entirely different sources:

- From rising damp: salts are often moved into the building fabric by rising damp. Salts migrate from the ground upwards into the wall fabric, resulting in salt deposits on or under the surface. These can often be seen as white salt deposits on the bricks, stone or around mortar beds.

- As a byproduct of burning: the black soot in the chimneys, a by-product of burning, is also very rich in salts. Over the decades, as the building ages, salts from the soot gradually migrate into the mortar bed and wall-fabric, reaching the internal plaster, resulting in flaking, crumbling or discoloration of the plaster. Damp patches created by salts - in contrast with water ingress - have less defined, hazy, fading edges. The problem also has a somewhat seasonal aspect, tending to fade away during warm weather and reappear after periods of rain.

Many “mysterious” dampness problems in the chimney area – despite the chimney stack being checked and cross-checked for leaks and none found – can be attributed to the chemical effect of chimney salts which attract and bond humidity from the surroundings.

External Walls

External walls can be subject to a multitude of dampness sources, making diagnosing the problem much more challenging, especially when multiple moisture sources overlap. Ground floor external walls are the most problematic being also subject to dampness from the ground.

Most common dampness problems that affect external walls, are:

- Water ingress: being part of the external envelope of the building, external walls are subject to rainwater ingress. Sometimes these can be difficult to find and trace as the entry-point of moisture can be different from where staining is visible.

- Broken pipes: broken or leaky pipes, although not very common, can cause similar symptoms to rainwater ingress.

- Water splash back [external ground-floor walls only]: rainwater often bounces back from the ground, splashing back and wetting the base of external walls, creating additional wetting of the wall fabric.

- Driving rain: wind driven rain, if long-lasting, can soak the wall fabric through, resulting in various dampness problems on the internal face of the walls. Tight pointing can alleviate such problems.

- Condensation: excess humidity in the building can condense (liquefy) on cold surfaces.

- Rising damp [ground-floor walls only]: walls sitting on the ground with non-existent or damaged DPC are subject to the evaporation of soil moisture, which long-term leads to rising damp that can cause significant damages.

- Hygroscopic moisture: salts present in the masonry can chemically bond moisture from the air or the underlying wall fabric, making water much more difficult to evaporate. Salts in external walls can originate from multiple sources: the soil (from rising damp), chimney areas (as a by-product of burning) or from the air (sea-spray, air pollution etc.).

Internal walls

In general, internal walls are subject to less moisture than external walls, being more sheltered. Most common moisture sources affecting internal walls are:

- Rising damp: the most common problem. Internal walls, just as external ones, are sitting on the ground, subject to the evaporation of soil moisture, which long-term leads to rising damp that can cause significant damages.

- Broken pipes: occasionally, pipes routed inside or under (internal) walls break, leading to water leaks. Leaking or broken pipes inside the ground can wet the soil and create intense rising damp signs in smaller localized areas.

- Hygroscopic moisture: salts present in the masonry can chemically bond moisture from the air or the underlying wall fabric, making water much more difficult to evaporate. Salts in external walls can originate from multiple sources: the soil (from rising damp), chimney areas (as a by-product of burning) or from the air (sea-spray, air pollution etc.)

Floors

Dampness problems affecting old floors depend to a large extent on the type of floor the building has.

The soil under suspended timber floors or traditional solid floors behave as large evaporative surfaces, that channel a lot of humidity into the living space. The excess humidity from the air is either absorbed by the hygroscopic salts on the walls or the floor, being recycled back into the wall fabric, or generate condensation on the evaporative cold floor and wall surfaces.

More modern solid concrete floors that act as vapor barriers, due to their strong mechanical resilience, usually don’t have too many dampness problems. However, due to their non-breathable nature they won’t let humidity evaporate from the soil, leaving excess humidity in the soil to be absorbed by the walls as rising damp. In other words, the humidity from the soil will be discharged by the walls instead, generally resulting in more intense rising damp in the walls.

Typical moisture problems affecting old floors are:

- Water ingress: old floors can “leak”. High water table from prolonged periods of rain or broken pipes can lead to liquid moisture penetration from the floor.

- Soil evaporation: old traditional floors are large evaporative surfaces, which can channel a lot of vapors into the living space. Although vapor moisture is invisible, high humidity can be measured or observed indirectly (e.g. rotting timber, mould, fungus growth etc.)

- Hygroscopic moisture: the high humidity from the air often ends up recycled back into the wall fabric by the crystallized salts that on the floor or the base of walls.

Cellars

There are several moisture sources affecting old cellars, the most common being:

- Sideways moisture penetration: is one of the most common dampness problem affecting cellars. The decay of the pointing or fabric can result in liquid moisture penetration or the fabric becoming soaked with moisture can result in vapor discharge into the internal space.

- Rainwater ingress: water can find its way through the floor, resulting in occasional flooding. Additionally, although not very common, rainwater can trickle down from the pavement into the cellar, soaking the upper areas of cellar walls.

- Rising damp: cellar walls being in contact with the ground are also subject to rising damp. In the presence of liquid moisture sources (e.g. sideways moisture penetration), rising damp often becomes completely "overridden" or invisible.

- Hygroscopic moisture: moisture ingress and rising damp both result in salt movement. Water can easily evaporate from the surface, leaving crystallized salts behind on or near the surface. These salts can chemically bond a lot of humidity from the air, recycling it back into the wall fabric, making dampness problems worse.

- Condensation: condensation and black mould are also often present due to lack of heating and high humidity in the cellar.

Diagnosing Dampness Problems - By Moisture Type

Here are some tips to easier diagnose dampness problems. Although a DIY hands-on approach is welcome, more complex problems can be best diagnosed by a competent professional.

Water Ingress or Leaks

Water ingress or leaks can be relatively easy to identify, as most of the time liquid moisture leaves obvious marks that often need immediate attention.

The point of moisture ingress often is not far from the moisture penetration point, making debugging easy. In some cases, however, moisture can travel quite a bit inside the wall fabric before resurfacing, making the penetration point discovery challenging. Traditional lath-and-plaster or plasterboard finishes often need to be stripped to aid discovery, although pinhole cameras can help to inspect enclosed areas.

Signs of water ingress or leaks:

- Damp patches on upper / higher areas of walls, away from the ground

- Damp patches on higher elevations, other than the ground floor

- Damp patches or crumbling of the wall / paint near or under flashings

- Cellar: inner face of cellar walls have a liquid water film, look shiny or damp at touch

- Cellar: the mortar in-between stones or bricks is soft, damp and mud-like

- Cellar: an area, corner or wall of a cellar is significantly damper/darker than the rest

Rising Damp

Rising damp can be diagnosed relatively easily as it affects mostly wall areas close to the ground, both internal and external walls. Typical signs of rising damp include:

- Tide marks at the base of walls

- White powdery salt deposits near the ground, on / under the surface or bricks, stone or mortar bed

- Crumbling of the paint and plaster

- Debonded, hollow-sounding plaster on lower areas of old walls

- Musty smell

Although in rare circumstances some of these signs can also be caused by water ingress (liquid moisture washing away and moving around salts in the fabric, especially in case of very old, thick stone walls - typically churches, large manor houses etc.), here are some additional signs which when present indicate with great certainly the presence of rising damp in a building:

- Dehumidifier extracting large amounts of moisture from the room or area (0.5 litre / day or more)

- Rising damp signs on internal or sheltered walls (tide mark, damp patches, salt crystallization, crumbling or bubbling of the paint or plaster etc.).

- High amount of nitrates (type of salts) in the wall fabric, based on a professional salt analysis.

Rising damp is often misdiagnosed, being labeled condensation or water ingress. The reasons for this are:

- False information on the internet stating that rising damp doesn't exist. Those who believe this statement without examining the facts and latest research, get confused and start chasing something else. Do your own homework on the matter.

- Rising damp being overridden by other moisture sources: when a wall area with rising damp is also subject to liquid water ingress, liquid moisture will often override the less abundant rising damp. Fixing the water ingress still leaves rising damp active in the background, creating issues later. Examining other areas of the building free from other moisture sources can help to decide to what extent rising damp is present in the building.

Here are some photos of rising damp is various buildings.

Condensation

Condensation occurs when moist air (usually warm moist air found indoors) comes in direct contact with colder surfaces (e.g. walls, window panes). It is more prevalent at the bottom of external walls and cold corners or in places where moisture stagnates - in areas with little or no ventilation (e.g. behind furniture).

During condensation, water changes its state from vapour to liquid.

Be aware that there are no-condensation situations, when a building or wall is in thermal equilibrium (no temperature differences, no warm-cold interaction). Without hot-cold interaction there can't be condensation so don't look for one. Example of such cases:

- Unoccupied, unheated buildings in thermal equilibrium

- External unheated walls (e.g. garden walls)

The concept "rising damp is condensation" because vapors condense inside cold walls is incorrect. Research and extensive measurements have conclusively shown that the core of old walls is warmer than their surface, the surface being the coldest area of a damp wall due to the cooling effect of ongoing surface evaporation. The wall fabric stores and retains heat in depth, just as the soil under the surface is warmer than its surface, even in wintertime - ground source heat pumps utilize this heat to heat buildings. So the rising damp is condensation idea does not check out under scientific investigation.

For condensation to exist, the following conditions must exist in a building:

- Moisture accumulation causing relatively high indoor humidity: this can happen either because too much humidity is being generated indoors (e.g. by cooking, showers, drying clothes) or dumped indoors by evaporative surfaces (e.g. walls with rising damp or old floors evaporating humidity), or too little ventilation (e.g. sealed buildings) to dispose of the humidity fast enough.

- Cold surfaces: most often due to poor wall insulation are present on which excess humidity can condense.

When faced with condensation, instead of just increasing the heating or ventilation, the right action to do is:

- Do a proper investigation to find out the root cause of the problem what is causing the condensation. Is there too much humidity? If yes, where it is coming from, what is causing it? If humidity is normal, are the walls too cold? Why? Important is to get to the bottom of the problem, which can be done by proper investigation.

- Base your action plan on the investigation data, instead of just poking randomly around. You can try some common sense actions to try to overcome the condensation problem, but often there are just too many variables to play with. Get in touch for a professional survey if needed.

Hygroscopic (Bonded or Chemical) Moisture

Certain materials can bond humidity present in the wall fabric or air, making moisture problems worse. Various salts (chemical materials found in the ground, air and water) and other materials (e.g. gypsum which also contains salts) present in/on the building fabric can make the wall fabric more liable to bond moisture.

Most common sources of salts in an old building are:

- From the soil: as rising damp and sideways moisture penetration in cellars.

- From the air: near sea side as sea spray, fog or wind carrying tiny salty water droplets. in busy towns fumes contain tiny particles of soot (from Diesel and various industrial processes), giving a dark patina to old buildings.

- Modern cement plasters that contain gypsum and salts (as an additive to slow down the drying of cement) planting the "seeds" of future salt crystallization into old buildings if moisture present.

- Old building materials: some old plasters have been mixed with sea water which degrades much faster than lime plasters mixed with freshwater.

Most common areas in a building where salts are likely to accumulate and create problems are:

- Lower 1 meter of ground-floor walls (both internal and external), as a result of rising damp

- Chimney areas: both ground floor and upper floors of chimney walls

- Traditional stone or brick floors laid on bare soil

- Internal face of walls, even at higher elevations, suffering from wind driven rain

- Cellar walls and floors

Signs of salt-related dampness problems:

- White or yellow salt crystallization (powdery deposits on the surface) on walls, cellar walls or floors.

- Peeling, dusty paint that leave marks when touched, or crumbling plaster.

- Damp patches with hazy, soft edges which come and go. Often on chimney walls.

- Darker discoloration of chimney walls (from light yellow to dark brown)

Most of the time these salts from the building fabric can't be removed but permanently remain embedded in the building fabric and they need to be managed accordingly using special breathable salt-resistant lime plasters.