Understanding the Basics

Before diving into the comprehensive topic of "solving rising damp", if you haven't done so, please familiarize yourself with the following pages, which contain important information about the movement of moisture and salts in the building fabric.

Without understanding the fundamentals of rising damp, the concept of solving rising damp becomes more difficult to understand - what is the right solution and why.

Two Problems – Water and Salts

Rising damp is of major concern because of the significant – often irreversible – damages it causes to old buildings worldwide.

Despite its name, emphasizing "dampness", rising damp is not just a dampness problem. Rising damp differs significantly from other dampness problems because of the presence of salts. Unlike rainwater ingress and condensation, which are “just” dampness problems, rising damp is a dual combined problem of dampness and salts.

Water is a problem, because it dissolves, transports and deposits the salts from the environment (soil, salty surface etc.) into the masonry, making it possible for the salts to damage the masonry.

Salts are also a problem because when they dry out, they crystallize and expand. Crumbling, flaking, spalling, powdering and other similar manifestations leading to the permanent damage of the wall fabric and plastering are all caused by the expanding salts.

Water in rising damp causes no damages to the masonry. A damp masonry, in the absence of salts, can undergo thousands of wetting-drying cycles and stay perfectly intact.

Between the two – water and salts – the crumbling of masonry induced by the salts is probably the most pressing problem of rising damp. The role of water is often less obvious as it operates invisibly in the background, diligently piling up the salts, indirectly contributing to the decay problem.

If salts are the show master, water is definitely its obedient silent servant.

From the above we can conclude the following:

- The damage of the plaster is just a consequence of the underlying dampness problem, which in combination with salts causes the decay of the plaster.

- Replastering – although it makes the walls temporarily presentable – can only be regarded as a temporary solution, as the underlying dampness in conjunction with the salts, will sooner damage the plaster again.

The Full Solution to Rising Damp

In solving rising damp, both the problem of dampness and salts must be addressed. An effective long-term solution to rising damp:

- Stops (or at least minimizes) the rising water flow, thus putting an end to the ongoing build-up of salts, and

- Uses the right materials and practices that can deliver a long-lasting renovation without causing additional problems to the masonry (sympathetic renovation).

Thus, the full solution consists of the following 2 steps:

Step 1 - Installing a DPC

Latest technical research on the mechanism of rising damp has uncovered that rising damp is not only capillary action but a combination of capillary action and vapour movement. Even more, rising damp can be created by vapour movement alone, even if no capillary action is present.

The primary role of a damp proof course (DPC) is to form a vapor (and liquid) barrier, to limit the evaporation of moisture from the soil into the wall fabric. It would also cut down the build-up of salts..

A damp proof course can be created by physical, chemical or electromagnetic means. Several DPC technologies exist on the marketplace, including non-invasive magnetic DPCs.

Step 2 - Breathable, Building-Friendly Renovation

To repair the salt-induced damages and to ensure a long-lasting finish, a certain amount of renovation is usually necessary. During renovations special attention needs to be paid to the presence of salts, and the plastering solution MUST contain a salt-barrier to prevent the premature breakdown of the new plaster. Just because a plaster is breathable it does not make it salt resistant.

Let's look at both of these steps in more detail.

1. Damp Proof Courses (DPCs)

Fully solving rising damp involves the fitting a damp proof course as part of the remedial works. Other actions - such as fitting drainage, having heating and ventilation, replastering with lime etc. - are NOT a substitute for a damp proof course, and as a result, despite the improvements they make, they won't won't cut down the build-up of salts water and salts into the masonry.

Although most technologies on the marketplace are invasive, non-invasive alternative also exists - the magnetic DPC being a modern, efficient and hassle-free, non-invasive option.

Several damp proof course technologies exist. These all differ in implementation, efficiency and longevity - here is a short development timeline and summary of each.

Types of Damp Proof Courses

The technology of damp proof courses has constantly evolved. Each DPC technology was a natural evolution over its predecessors, attempting to improve and simplify the application process, while also addressing some of the shortcomings of previous generations.

Click the titles below to read more about various damp proof courses.

Based on written historic records, original physical DPCs date back to around the 1840s, possibly earlier. They were the first attempt to solve rising damp during times when buildings were generally erected on the soil. After a few decades or centuries this resulted in rising damp, causing fabric decay, high humidity, health issues etc.

The most common materials used for damp proof courses in the Victorian age were slate bedded in cement, hot asphalt, sheets of lead, glazed bricks and vitrified stone-ware tiles.

As we already know today, these "original" damp proof courses lasted anywhere from a few decades to about a century, eventually failing as they aged, as the lifetime of a damp proof course is shorter than the life expectancy of a building.

Technical solutions had to be found to retrofit old buildings with new DPCs in order to keep rising damp in check.

The first attempt to repair aged, decayed DPCs that reached their end of life, was to add impervious (e.g. blue engineering) bricks to the base of the walls, or to cut the walls with a large chainsaw and drive stainless steel plates into the cut - a very invasive and labor intensive task.

Technical advancements in chemistry made the retrofitting process involving solving rising damp simpler and less invasive by injecting waterproof chemicals into the walls. This reduced the workmanship to a few drilled holes every few inches. Nevertheless, the injection process was still fairly invasive, leaving permanent blemishes on buildings, while giving variable results, performing poorly on thick solid walls with rubble filled core.

Further technical research into molecular phenomena and a better understanding of electrokinetic phenomena made possible a newer, smarter, less invasive approach to solve rising damp, by applying a small voltage to the walls through embedded wires.

But it was not all perfect, the main reasons why electro-osmotic DPCs failed over time were the corrosion or physical damage to the wires (as shown below), and more importantly, more recent findings have shown that in high salinity environments (e.g. old, porous, salt-laden walls) electro-chemical effects in the masonry rendered many of these systems ineffective.

Magnetic DPCs attempted to address the shortcomings of electroosmotic DPCs. New discoveries about Earth's energetic background, as well as advancements in radar and telecommunications technology, paired with some clever practical electronic engineering resulted in the elimination of the trouble-prone wires - providing a truly contactless, non-invasive and hassle-free solution to rising damp.

A magnetic DPC unit that looks like a small lampshade and it can cover the whole building, You can read more about the Magnetic DPC technology here.

DPC Longevity, Breakdown

Just like anything else, damp proof courses are also liable to aging and deterioration over time. Immense mechanical pressure, vibration, corrosive salts, microorganisms, frost action etc. are just some of the elements that cause damp proof courses decay over time.

The life expectancy of a damp proof course depends on the type of materials used and quality of the workmanship. Based on our experience, most DPCs if done correctly, can last anywhere between 50-100 years.

In the vast majority of cases one won't be able to assess the condition of a DPC by visual inspection, as 95% of it is hidden inside the wall. Instead, assessing the condition of the wall and plaster above the DPC level can give one indication about the condition of the underlying DPC.

As a rule of thumb: if the wall shows signs of rising damp above the DPC line, especially on sheltered internal walls, with no other moisture sources present, then the damp proof course is likely to be compromised.

Here are some examples of damaged or broken down damp proof courses.

2. Building-Friendly Renovation, Replastering

After the installation of a damp proof course, renovation is the second major phase in the handling of rising damp.

The main challenge in renovating after rising damp is the presence of SALTS.

Walls affected by rising damp often contain a significant amount of ground salts. These salts have been drawn up by the rising damp and deposited into the wall fabric over many decades or centuries. When salts crystallize, they expand in volume, leading to the breakdown of the wall fabric. Crumbling, flaking and loss of building fabric are primarily caused by salts, not water.

Plaster Life Cycle

Here is the typical life cycle of a fresh coat of plaster applied onto an old wall. Here are the reasons and the mechanism of why plasters break down and need to be reapplied periodically.

- Fresh plaster applied: the old wall fabric under the plaster often contains a lot of salts, the main variables being the salinity of the soil and the age of the building.. Generally, the older the building, the more salts are present in the fabric. When fresh plaster is applied onto the wall, the water from the plaster dissolves these salts, which start migrating into the freshly applied plaster, which becomes contaminated by these salts.

- Salt crystallization starts: as the plaster dries, the salts also start drying and crystallizing. Because plasters have some porosity (e.g. free internal space inside the plaster), the crystallizing salts start expanding into the internal pores, filling up the pore structure (see image above).

- Salt accumulation: in lack of a DPC, rising damp keeps piling up more and more salts into the building fabric. Heating and ongoing evaporation moves the salts from the depth of the fabric near the surface (especially if the plaster is a breathable lime), resulting in the accumulation of salts inside the plaster. As long as the pores of the plaster have enough internal space to hold the expanding and crystallizing salts (known as subflorescence), the plaster stays visually intact.

- Plaster breakdown: once the pores of the plaster get filled with salts, mechanical pressure starts developing, leading to the cracking and crumbling of the plaster, Salts can also crystallize on the surface, forming a white powdery coat, known as efflorescence.

Crystallizing salts are the primary reason behind the decay of the plaster and wall fabric

This cycle can occur faster or slower, depending on a number of variables such as the soil salinity, age of the building, pore structure of the wall, type and hardness of plaster, environmental conditions etc - all these conditions determining how long the plastering will last. In certain conditions the breakdown can be fairly quick (months, not longer than 1-2 years) or much slower (years).

As long as the building has no DPC and the underlying water flow is present, the plaster damage will reoccur. This leads to an ongoing, never-ending replastering cycle for old buildings, repeating every few years, costing time and money.

How Various Plasters Perform?

Although we have covered the different types of plasters in another section, here is a quick summary about how various plasters types behave in the presence of humidity and salts, and how suitable are they for the renovation of old buildings.

- Lime plasters: the oldest type of plasters in human history. They have a rich heritage going back several thousands of years. Practically all buildings built before the Industrial Revolution (before the early 1800s) have been built with lime. The have many desirable properties that make them the right choice for old buildings. On the other hand they behave poorly and degrade quickly in the presence of high humidity and salts.

- Volcanic lime plasters: to increase the water and salt resilience of lime plasters, first the Phoenicians then the Romans have developed special lime mixes that perform extremely well in very humid, high-salinity environments. Mixing volcanic sands and ashes to lime resulted in highly breathable yet salt-resistant lime plasters that can survive in sea water for decades or centuries without breakdown. These plasters are extremely suitable for replastering wall affected by rising damp and salinity, without affecting the wall fabric's breathability.

- Natural hydraulic lime (NHL) plasters: because volcanic ingredients were expensive and not available everywhere, common clay has been used to give lime better water resilience. NHL plasters use made of impure lime stone containing lime and clay, resulting in lime plasters with better water resistance, but with less breathability.

- Cement plasters: are modern plasters developed from the mid-1800s. Lime stone, mixed with a high content of clay, similar is burnt at very high temperatures that results in a strong, non-breathable plaster. Cement plasters have good water and salt resistance, but being not breathable they should not be applied on old buildings.

- Renovation plasters: are specially developed cement-based plasters for the renovation of rising-damp affected salty walls. They contain chemical additives to minimize the effect of salts. Chemical damp proofing companies use these types of plasters extensively, but they are non-breathable or have limited breathability.

- Gypsum plasters: they are the mainstream finishing plaster in modern buildings, being cheap, easy to work with and give a pleasant smooth finish. They behave very poorly in the presence of water and salts. They are applied on top of cement plasters; they should not be applied on top of lime plasters because they contain salts, which long-term leads to the breakdown of lime.

For the renovation of old buildings one should use traditional lime plasters, and should avoid modern cement and gypsum plasters.

Salt-Resistant Lime Plasters

Nothing lasts forever, however in lack of salts and excess humidity a good quality lime plaster should last decades, not just a few years. Salts are the main reason behind the premature decay of plasters.

To efficiently deal with the problem of salts and to extend the life expectancy of plastering, special salt-resistant lime plasters have been developed.

The technology of traditional salt-resistant lime plasters originates from ancient Rome. Being outstanding architects and builders, the Romans have experimented extensively with lime, formulating many plaster mixes that stood the test of time. They have discovered that by adding volcanic ashes and sands to lime, they can significantly improve its water and salts resistance, while retaining its breathability.

The most common materials added to lime were pozzolans (volcanic soils or rock fragments) and cocciopesto (milled bricks or terracotta fragments). These reacted chemically with the free lime, forming water resistant compounds. Such mortars were able to harden quickly not only in the presence of water but also underwater in the total absence of air, and they are known as hydraulic mortars. They have been extremely popular in Venice, well suiting the humid and aggressive environment of the Venetian lagoon.

Salt-resistant plasters were historically used in Venice

The study of historical writings and an extensive technical research program resulted in the development of the Rinzaffo MGN salt resistant lime plaster, based on the ancient Roman technology. It is breathable, waterproof (stops liquid water but allows the passage of water vapors) and salt-resistant, being an efficient salt barrier stopping all types of masonry salts (sulphates, nitrates, chlorites).

By keeping the salts away the longevity of the plastering can be increased significantly.

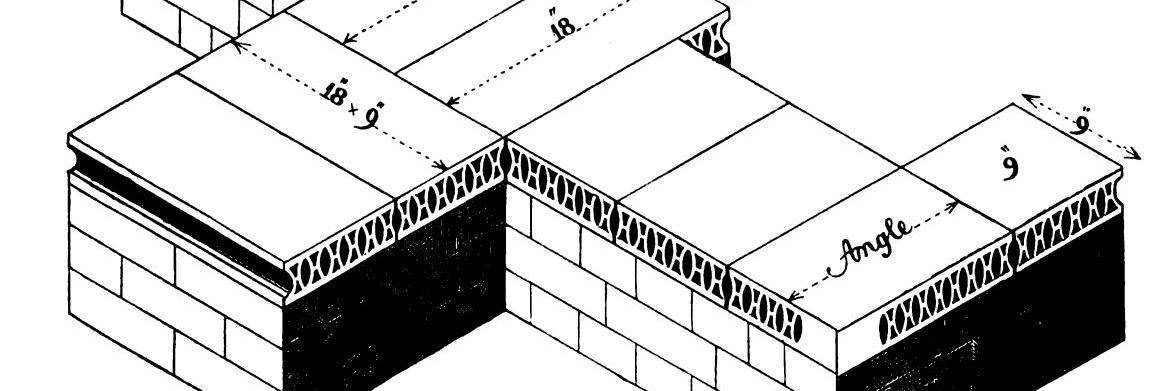

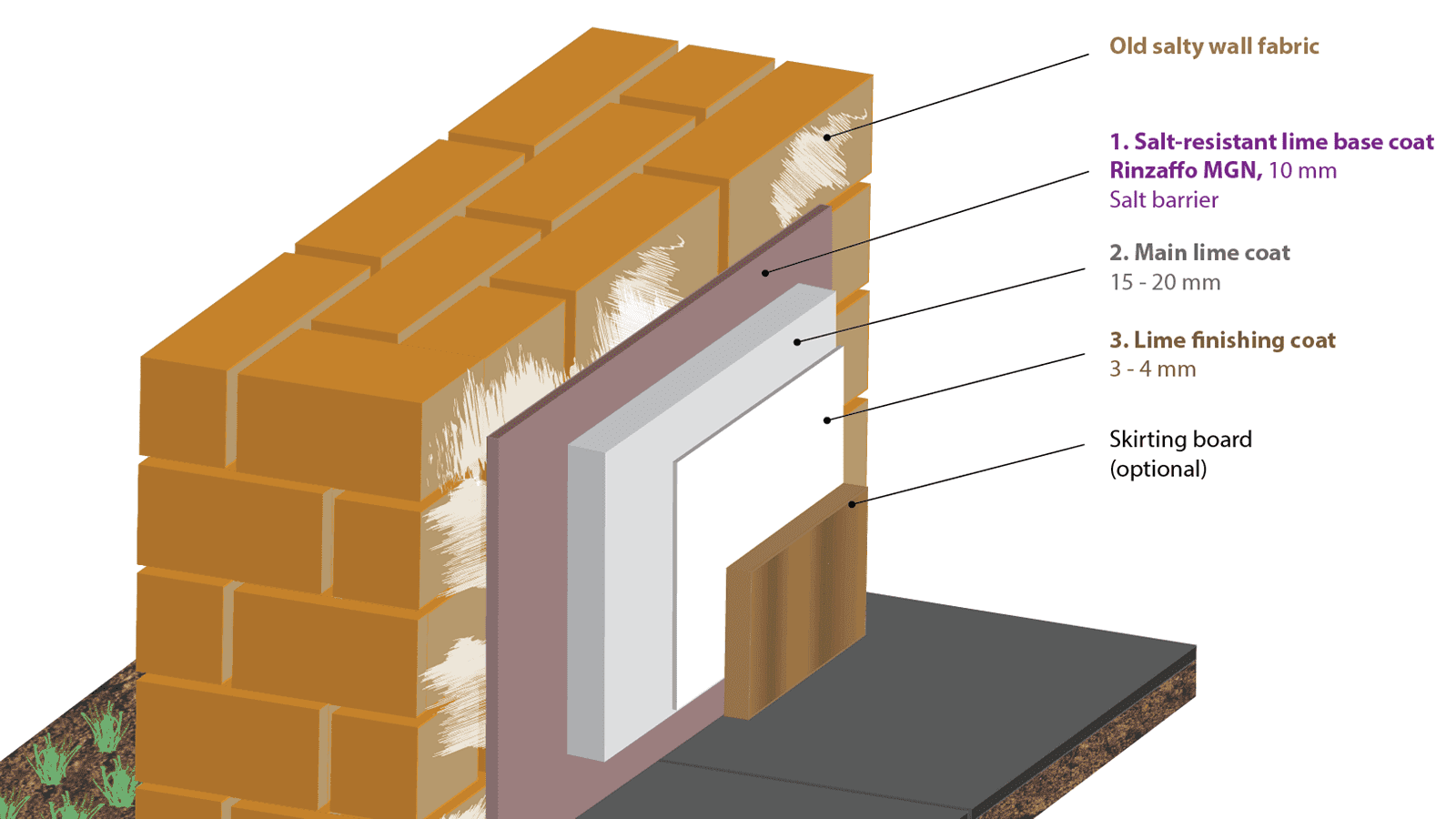

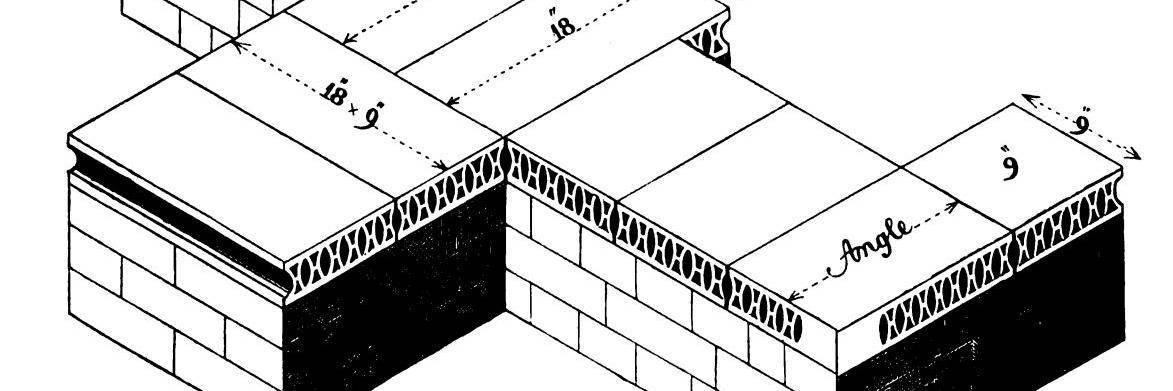

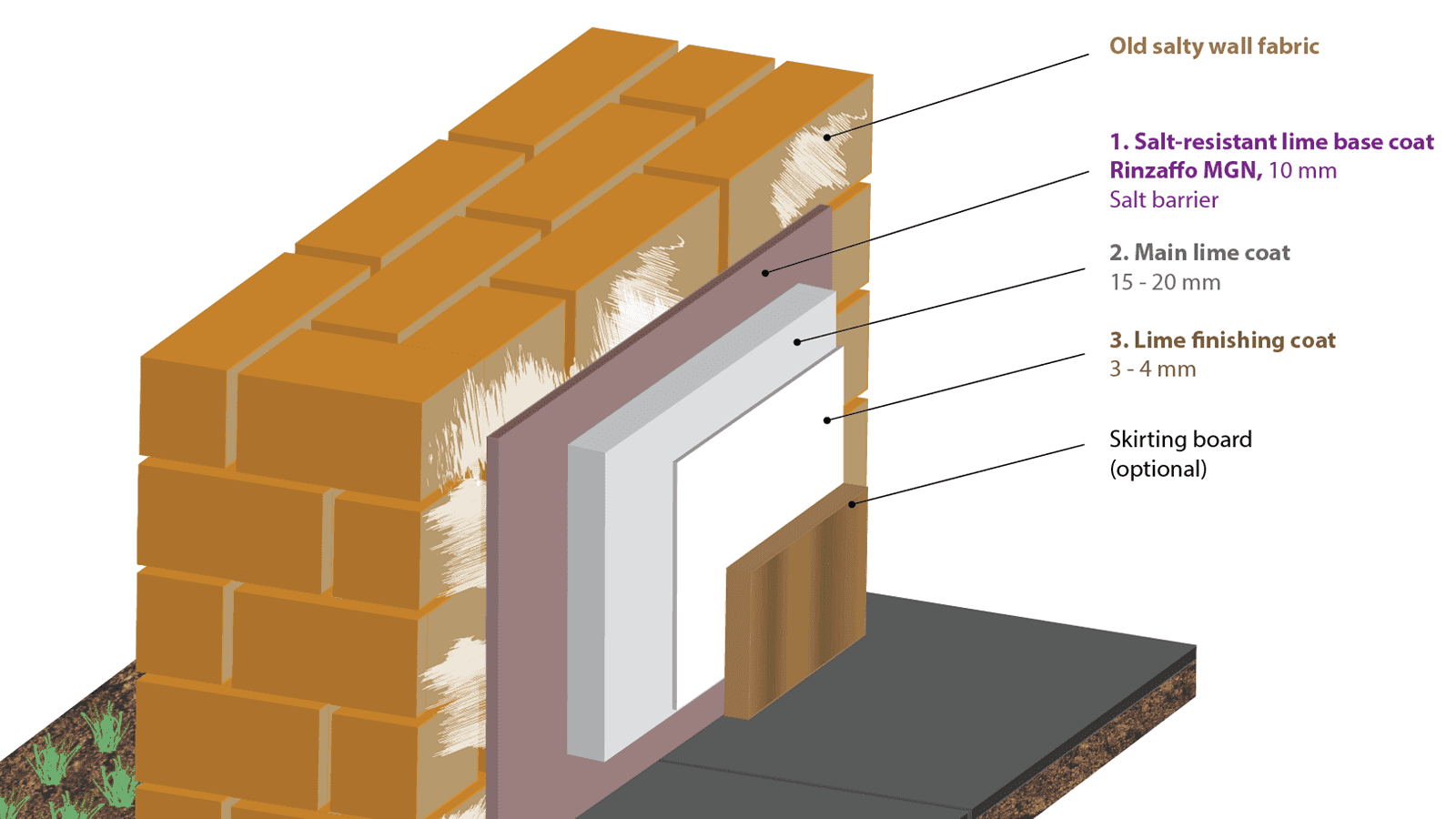

Plastering Schedule

To provide a building-friendly long-lasting plastered finish to old walls affected by rising damp and/or salts, the following plastering coats are recommended:

- Salt-resistant lime base coat: [10 mm]: the very important role of this base coat is to prevent the premature decay of plastering, increasing its longevity by 5-10 times. The Rinzaffo MGN salt-resistant base coat's internal pore structural is formulated in a way to block (larger) liquid water and salt molecules, while letting (smaller) water vapors molecules through, facilitating evaporation.

- Main lime coat [15-20 mm]: a good quality lime plaster such as Calcina Bianca MGN, a premixed lime plaster based on the highest purity aerial lime (over 90% calcium hydroxide), a small quantity of natural hydraulic lime and washed river sands without impurities.

- Lime finishing coat: [3-4 mm]: a good quality lime finish such as Calcina Fine MGN is a premixed white lime finishing plaster based on the highest purity air lime (min. 90% calcium hydroxide).

- A breathable paint: such as lime wash or mineral paints.

Plaster coats used after rising damp

Plasterboarding

Plastering is not the only way to renovate and finish old walls. In addition to the above described plastered finish, plasterboarding is also an alternative for a more modern looking finish.

Plasterboarding is the modern version of the Victorian lath and plaster technology, and it is an easy, fast, cost-effective solution for renovating after rising damp, that can be applied on older building,

One important note here: dot-and-dabbing MUST be avoided. Dot-and-dab, also known as drylining, is a popular low-cost plasterboarding technique that involves the gluing of the plasterboard directly onto wall surfaces. Walls finished in this way can be painted almost immediately, resulting in time savings for tradesmen.

Although a budget-friendly option, it should be avoided on any external walls (due to condensation and penetrating rain) or on any walls prone to dampness and salts (e.g. ground floor walls, or walls with rising damp or following a rising damp treatment) as over time moisture and salts can migrate through the glue into the plasterboard, resulting in surface damp patches, ruining the finish.

Instead, the plasterboard MUST be mounted on battens, preferably galvanized steel battens. You can read more about plasterboarding here.

Plasterboard mounted on metal battens - The right way to do it

Incomplete Solutions

There are a number of other common solutions to rising damp – both traditional and modern approaches – which in our professional opinion are partial solutions only.

Some of these solutions, however, can be valid and justified in certain scenarios, as the chosen damp proofing solution must fit into the overall renovation concept for a given building. Damp proofing is just one of the many facets of a complex renovation project, and as long as one understands the benefits and limitations of each solution, can choose the most appropriate solution for a given project.

Traditional / Building Friendly Solutions

Click on the titles below to read more about each solution.

Lime plasters are preferred for the replastering of old walls as they offer the following important benefits:

- Breathable: they lets moisture freely evaporate out from the underlying (damp) wall fabric, preventing the excessive build-up of humidity.

- Porous: they stores in their pore structure the crystallizing salts, giving a dry, salt-free surface.

- Flexible: they don't crack.

Traditional lime plasters act as sacrificial plasters, absorbing the salts until their pore structure fills up, when they are broken down by salts. This sacrificial behaviour of lime plasters is a valid solution in many applications.

Limitations of the Solution

Despite of their breathability, sacrificial lime plasters perform poorly in very salty and damp environments, their life cycle decreasing in proportion with the increase of salinity. Their frequent replacement can also carry a significant cost element.

Replastering with lime also does not address the rising water flow and salt accumulation problem, being only half a solution.. But until broken down by salts, lime plaster can control rising damp in an building-friendly way, keeping surfaces dry and presentable.

Lime plaster ruined by salts in less than a year

Benefits

- Breathable, building friendly solution

Limitations

Drainage has an important role keeping buildings dry, by channeling away the liquid moisture flow from under/around the building.

Limitations of the Solution

Not all moisture is drainable; the bound moisture content of the soil can't be drained away. Just think of a well wrung clothing: that still contains a lot of moisture which can only be driven out by evaporation.

Lab test have shown that a fully drain soil contains more than enough moisture to cause rising damp. The evaporating soil alone can cause rising damp long-term even if there is no liquid capillary action present.

Drainage does not replace a damp proof course, and is best to be used, if possible, in conjunction with a DPC.

Benefits

Limitations

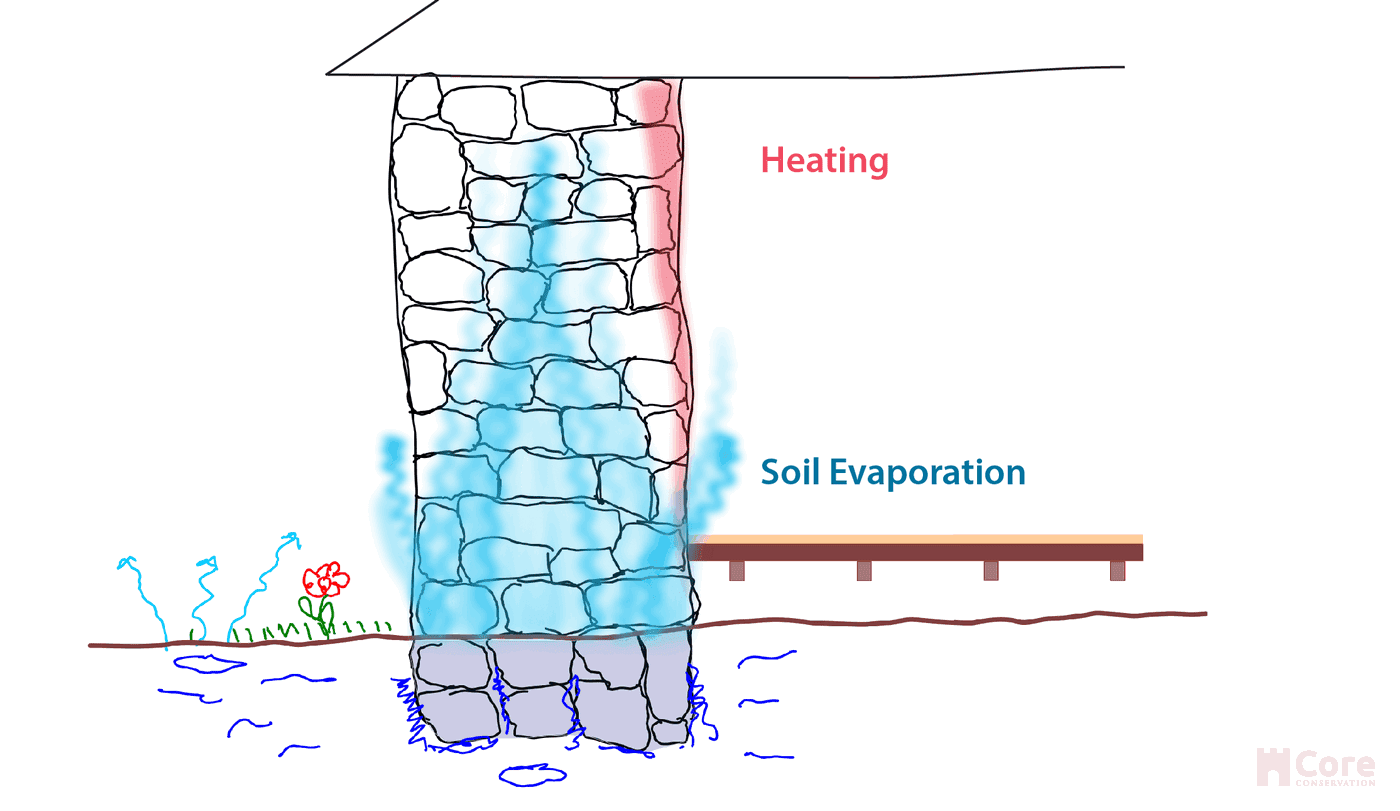

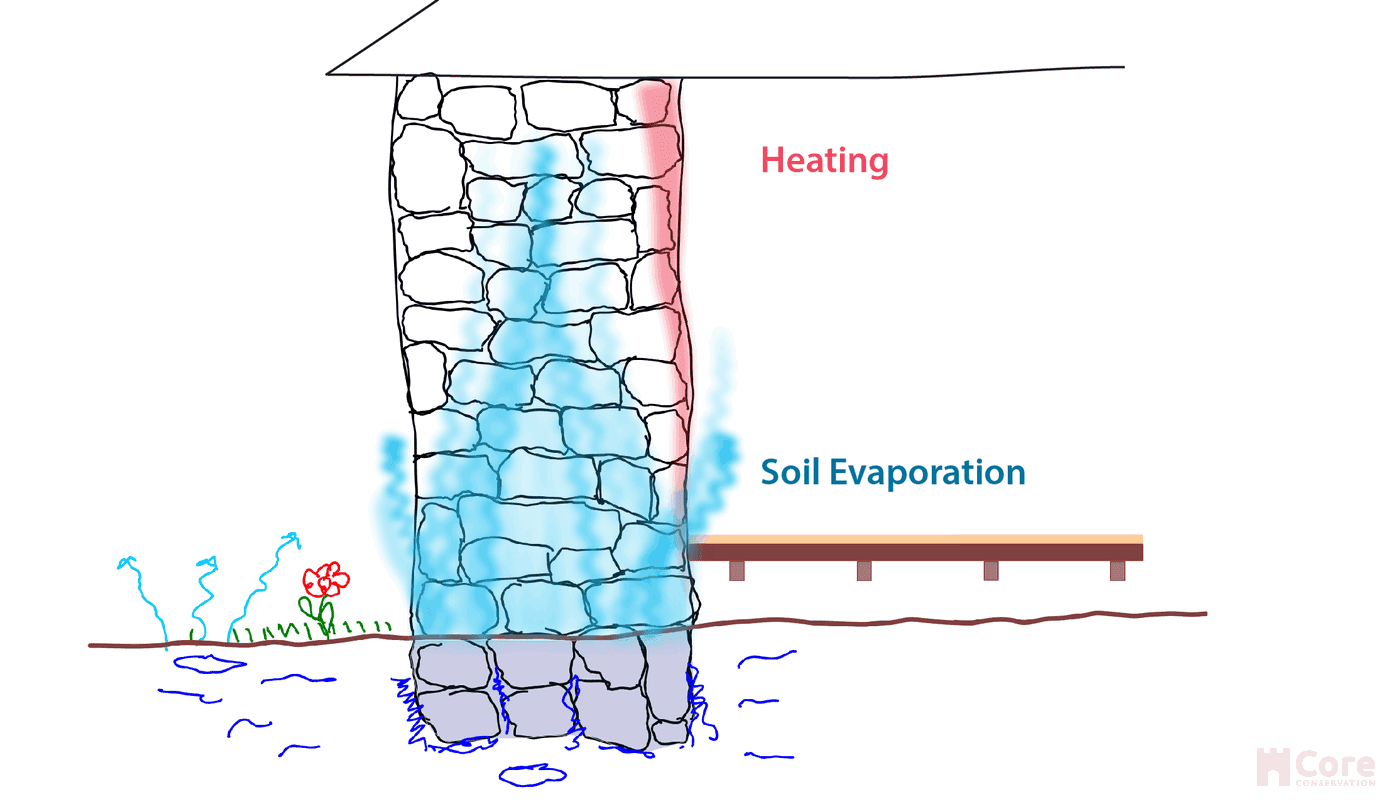

Heating and ventilation facilitates evaporation, but in the presence of rising damp they also have a secondary, undesirable effect.

Limitations of the Solution

In lack of a damp proof course, the bottom of the wall is connected to the water table (unlimited water supply). Evaporation creates a pressure difference which draws up more moisture and salts from the ground, creating an ongoing water intake from the ground into the walls. You can't dry out a masonry with an unlimited water supply at its base. The base of the wall must be detached from the water table first, for heating to become effective.

Lab experiments have also shown that in the presence of rising damp, the cooling effect of the ongoing evaporation from the soil renders heating ineffective near the base of the wall.

Soil evaporation overrides the effect of heating near ground

Benefits

Limitations

The combined effect of lime plastering, drainage, heating and ventilation creates a more significant impact onto the building than its individual parts, creating enough change in a building to be considered a solution on its own.

Limitations of the Solution

As mentioned earlier, this solution does not address the problem of rising water and salts. The longevity of the solution will depend on the salinity of the soil and building fabric and will be limited by the plaster's salt-storing capacity.

Pros

Cons

Modern Solutions

Replastering with modern cement plasters is a common way of replastering old buildings after rising damp.

Tanking is the application of some waterproofing material onto the surface of the affected damp walls in order to block dampness and salts, and to keep wall surfaces dry. Most common waterproofing materials are: cement plasters or slurries, bituminous coats, plastic membranes or special non-breathable cement-based “renovating” plasters, often with waterproofing or salt-blocking additives.

Limitations of the Solution

All solutions using modern waterproofing materials are non-breathable, causing the accumulation of moisture behind the waterproof barrier, making it rise higher in the background. The moisture accumulation long-term results in damages to the building fabric.

These solutions do not substitute a damp proof course. A magnetic DPC system can reduce the moisture content of non-breathable walls already tanked. Tanking should not be part of any rising damp solution as better alternatives exist.

Waterproof membranes on old walls accumulate moisture under the surface

Benefits

Limitations

Dot and dabbing is a “budget” plasterboard mounting technique that involves the gluing of the plasterboard onto the old (often salty or damp) wall surfaces.

Limitations of the Solution

Salts can easily migrate into the plasterboard through the plasterboarding glue, resulting in damp patches on the surface. In addition, thermal bridging through the plasterboard glue can create condensation patches, especially in case of solid walls subject to more cooling.

Plasterboarding the proper way, by mounting the plasterboard on timber or galvanized steel battens creates a long-lasting solution.

Without a damp proof course intended to stop the rise of water and salts, plasterboarding is just half a solution that hides the problem.

Dot and dab plasterboarding can result in damp patches in old walls

Benefits

Limitations

Skimming is a “budget” plastering solution, by applying a thin fresh coat of plaster on top of the old plaster.

Limitations of the Solution

The old plaster is often very salty. During skimming these salts are diluted and moved from the old plaster into the new one, causing its early breakdown due to salt crystallization.

Skimming of wall surfaces affected by rising damp or salts should be avoided entirely. Instead, the wall should be fully replastered, ideally using a salt-resistant base coat.

Replastering is only half a solution, as it does not address the problem of rising water and salts.

Skimmed wall surface ruined by salts only 6 months later

Benefits

Limitations

Waterproofing paints are a short-term quick-fix to hide starting rising damp problems.

Limitations of the Solution

Repainting does not address the problem of rising water and salts.

Over-painting affected areas won't last, they need to be repainted every few months as the underlying salts keep destroying the paint and the plaster. The peeling paint indicates salts in the plaster, which needs to be replaced for a permanent fix.

Benefits

Limitations

As we can see, many of these solutions try to overcome the rising damp problem without using a damp proof course, due to the invasive nature of DPC technologies. As a result, they try to go around the invasive DPC problem and substitute it with more building-friendly, less-invasive actions.

None of these actions substitutes a missing damp proof course. DPCs have a very specific role, they act as a vapour and liquid barrier that stop moisture accumulation from under the wall.

Due to technological advancements a non-invasive DPC technology exists. We are going to cover the magnetic DPC technology in the next section.