Rising Damp – Different Viewpoints

Amongst all moisture-related problems rising damp is probably one of the more controversial topics in the UK. As mentioned on the previous page, an important piece of the puzzle - that vapour movement alone, without liquid moisture, can cause rising damp over time - was missing for decades, creating an industry-wide confusion on this subject.

This in the building industry resulted in conflicting viewpoints on the subject (e.g. rising damp doesn’t exist, it's extremely rare, it can't be found etc.) making this topic even more difficult to comprehend, especially for non-professionals.

The good news is, the situation is much simpler. Although rising damp is a complex phenomenon involving vapours, liquids, salts etc, there is a solid global consensus (throughout Europe and worldwide) that rising damp is a common occurrence, it is a problem, and it causes significant damages to old buildings. Other viewpoints thinking this otherwise are also explored in detail here.

On the following pages we would like to explore in depth both viewpoints and thus hopefully bring more clarity into this subject, so you can decide for yourself whether rising damp should be considered or ignored.

Present-Day Scientific Viewpoint

As most scientific research these days is carried out by Universities and independent research establishments, the viewpoint on "academia" on this topic is considered highly relevant and authoritative. Let’s see what is the viewpoint of universities on rising damp.

1. Academic Research Papers

By exploring the scientific literature one can find hundreds if not thousands of university research papers from highly-trusted sources describing many aspects of rising damp in detail.

The world's largest peer-reviewed research platform, Elsevier ScienceDirect, at the time of this writing lists 579 peer-reviewed research papers about rising damp. Another highly regarded research portal, Web of Science, lists 236 research articles on rising damp.

Peer reviewed papers, which have been checked by other researchers or experts of a field for technical accuracy, are considered a highly trusted source of information.

Here is a selection of research papers on rising damp with links to the original source publications. The abstract (short summary) of these papers is freely available. Full-text versions in most cases require a subscription, however some full papers are freely available under the open science framework.

- Effectiveness of methods against rising damp in buildings: Results from the EMERISDA project, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2018

- State-of-the-art on methods for reducing rising damp in masonry, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2018

- Rising damp removal from historical masonries: A still open challenge, Construction and Building Materials, 2013

- Rising damp: capillary rise dynamics in walls, Royal Society UK, 2007

- Evaluation of mortar samples obtained from UK houses treated for rising damp, Construction and Building Materials, 2011

- Rising damp in historical buildings: A Venetian perspective, Building and Environment, 2018

- The influence of the thickness of the walls and their properties on the treatment of rising damp in historic buildings, Construction and Building Materials, 2010

- Efficiency evaluation of treatments against rising damp by scale models and test in situ, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2018

- Mathematical analysis of the evaporative process of a new technological treatment of rising damp in historic buildings, Building and Environment, 2010

- New test methods to verify the performance of chemical injections to deal with rising damp, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2018

- TDR-based monitoring of rising damp through the embedding of wire-like sensing elements in building structures, Measurement, 2017

- Geophysical and geochemical techniques to assess the origin of rising damp of a Roman building (Ostia Antica archaeological site), Microchemical Journal, 2016

- Evaluation of compatibility and durability of a hydraulic lime-based plaster applied on brick wall masonry of historical buildings affected by rising damp phenomena, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2002

- Effects of rising damp and salt crystallization cycles in FRCM-masonry interfacial debonding: Towards an accelerated laboratory test method, Construction and Building Materials, 2018

Here are some statements made by researchers about rising damp.

Rising damp is a recurrent hazard to ancient buildings in Europe and its relevance is expected to increase in the future, due to climate changes.

Effectiveness of methods against rising damp in buildings: Results from the EMERISDA project, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2018

Rising damp is one of the main problems affecting historic masonry buildings, as it leads to severe consequences, in terms of both bad indoor conditions (high air relative humidity) and materials deterioration. The phenomenon of rising damp is very common in ancient buildings.

State-of-the-art on methods for reducing rising damp in masonry: Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2018

Rising damp is an important cause of wetness in buildings. It is a cause of decay and deterioration in standing stones, monuments and at archaeological sites. Rising damp is a complicated process.

Rising damp: capillary rise dynamics in walls:

The Royal Society Publishing, 2007

Fresh or sea water rising damp in historical buildings is a well-known problem. Venice is the emblematic case of a historical maritime city affected by rising damp.

Rising damp in historical buildings: A Venetian perspective:

Building and Environment, 2018

Serious rising damp can lead to a building becoming inhospitable

due to mould growth, paint blistering, plaster crumbling and wallpaper separation. It is a vexatious and persistent problem requiring a great deal of effort and financial resources in addressing its manifestation, typically with varying degrees of success.

Evaluation of mortar samples obtained from UK houses treated for rising damp: Construction and Building Materials, 2011

In old buildings, rising damp in walls that are in direct contact with the ground leads to the migration of soluble salts that are responsible for many of the pathologies observed.

Construction and Building Materials, 2010

2. Professional Textbooks

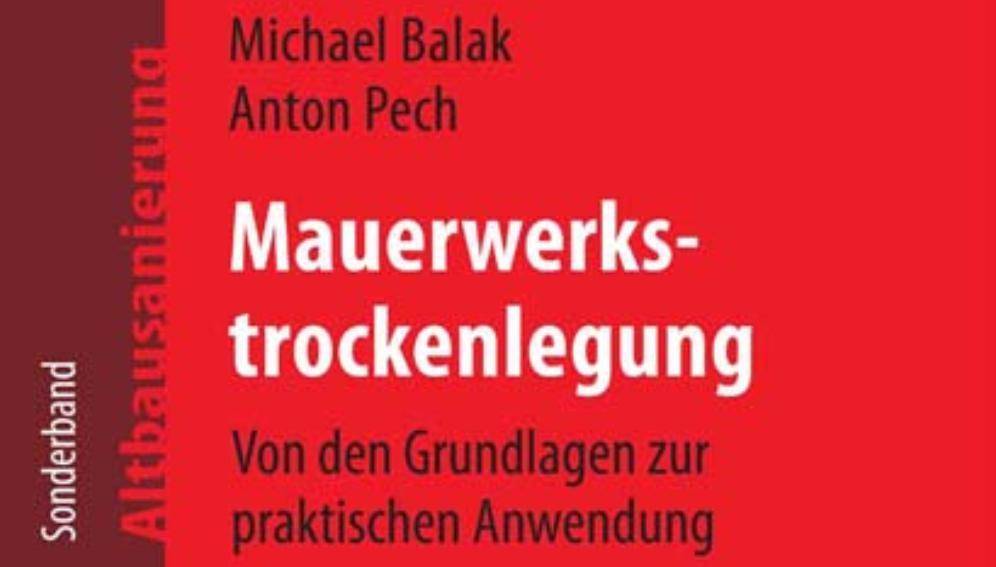

Some professional textbooks, such as this 270-page Austrian technical reference book "Building Dehydration - From Basics to Practical Applications" published in 2017, discuss in detail many aspects of wetting and drying as well as the basics of moisture movement and building Physics.

The book also describes in detail the development of rising damp as a result of various vapour and liquid transport phenomena. The book makes a clear distinction between rising damp and condensation, which are two different phenomena.

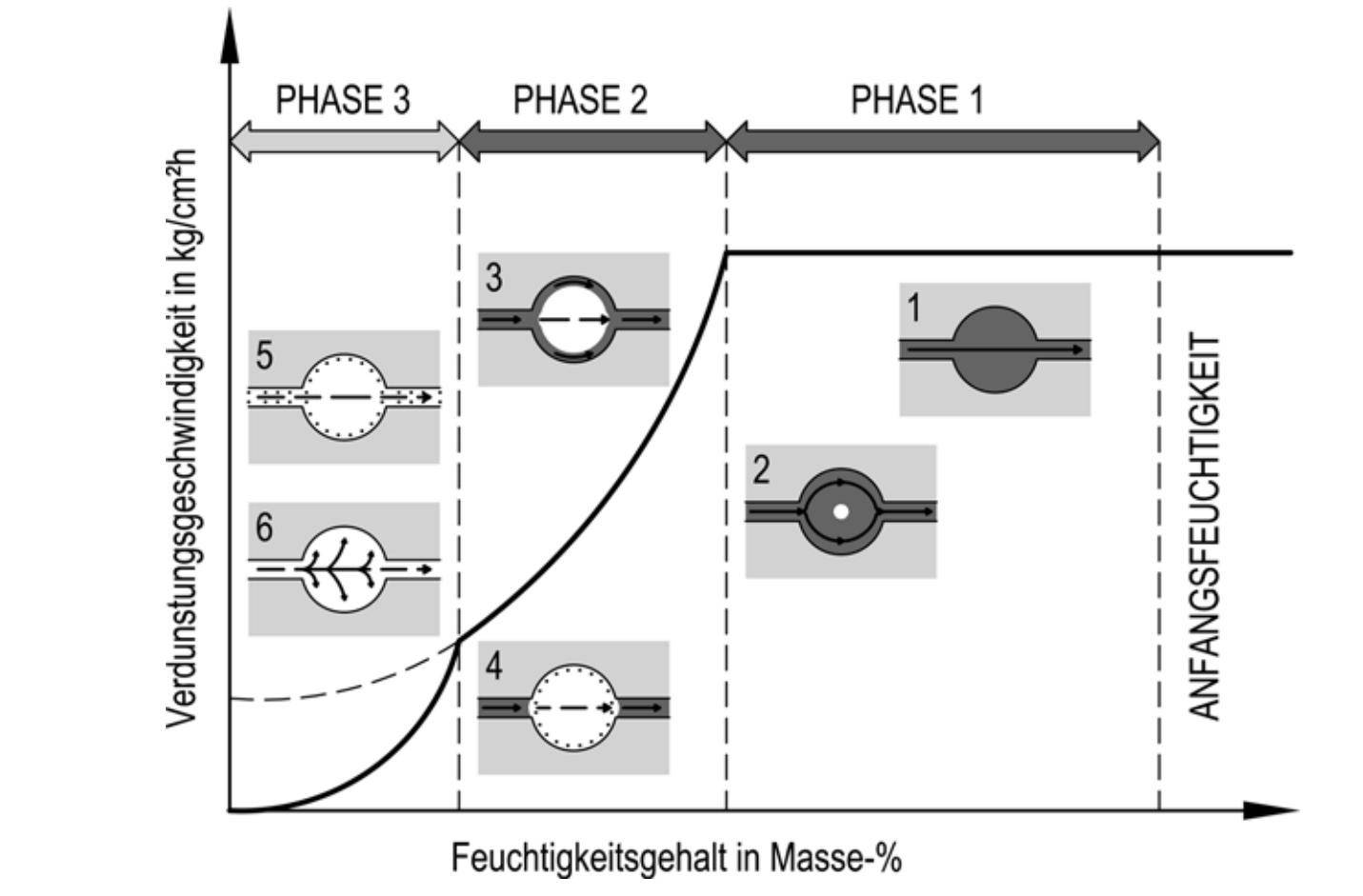

Development stages of rising damp

The stages of dehydration and various mechanisms that contribute to the dehydration of the building fabric are also presented in a logical and structured way.

Masonry dehydration phases

3. Lab Experiments

Rising damp can be recreated in an artificial lab environment very easily. This is being done regularly in many research labs as part of the ongoing research. Some of the research papers listed above contain actual photos of rising-damp related lab experiments such as the one here.

Rising damp recreated in a lab

As part of our in-house research program we have also recreated rising damp in our own labs. In our observation, in order to get decent results, it is important to use porous "old-style" bricks. Harder, modern or less-porous bricks have much slower moisture uptake, which might explain some past failures to recreate rising damp successfully within the experimental time-frame.

By using "old-style" but otherwise new porous bricks purchased from a brickyard, we managed to get water rise to about 1 metre high within 4 days. Here are our figures:

- The water has risen to the top of the first brick (200 mm) after 2 hours

- To the top of the 2nd brick in 14 hrs

- To the top of the 3rd brick in 35 hours (1.5 days)

- And to the top of the 4th brick (850 mm high) after 4 days

All this occurred in a condensation-free, uniformly-heated, protected environment.

We captured the whole process on a time-lapse camera - take a look, it looks pretty cool.

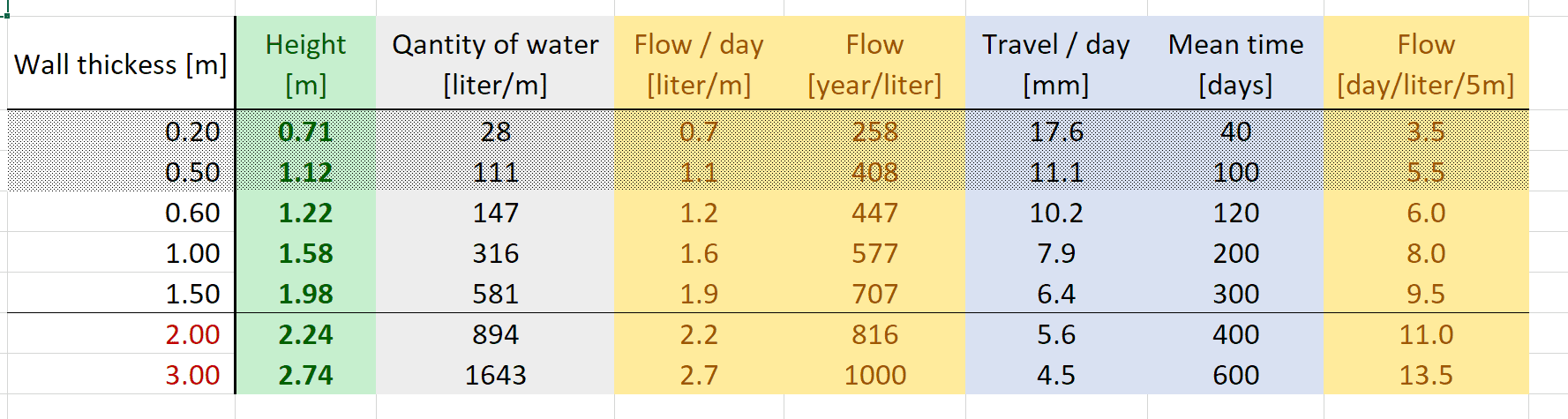

4. Calculations - Facts and Figures

The amount of water that old walls can accumulate from the ground can be truly staggering.

One of the scientific papers listed above, published by the Royal Society of London provided the formulas to calculate some of the key parameters of rising damp. These calculations included:

- The rise height of rising damp in a wall (steady-state height)

- The amount of water inside the walls per linear metre of wall section

- Daily water pass-through rate: how much water is "moving through" a wall every day, year etc.

- Water travel time (residence time): the average time for the water to move through the wall fabric from the base to its evaporation point (exit point)

Being a research paper published in the UK, all figures were given for UK climate conditions, and the numbers are really interesting. Here are some of the key figures for a somewhat "average" 500 mm thick wall:

- Rising damp height: 1.12 metre

- Quantity of water stored by each metre of wall section: 111 litres

- Water "flowing" through the wall: 1.1 litres/day/metre wall section. This translates to 408 litres/year for each metre of wall section. No wonder your dehumidifiers get filled quickly.

- Water travel time through the wall fabric (residence time): 100 days to travel through the wall, from the very bottom to the evaporation area (rising damp height).

I have verified these calculations in Excel, running a few "typical" scenarios for comparison purposes, to better understand how rising damp behaves at different wall thicknesses. Here are the calculations:

Calculations about how rising damp impacts walls of different thicknesses

What these figures tell us, what can we conclude:

- Thicker walls hold much more water than thinner walls due to their much larger volume. In simple terms, you can think of a thick wall as large bucket, and a thin wall as smaller bucket. Additionally, larger walls are in contact with the ground via a larger footprint, so the water intake of thick walls is much more significant.

- Rising damp height increases with wall thickness: rising damp rises until water reaches equilibrium, determined by the balance of water intake (water in) and evaporation (water out). If we consider the same evaporative surface (e.g. 1 sqm), a lot less percentage of water can evaporate from a thick wall than a thin wall, resulting in higher rise height.

The height of rising damp in residential buildings with thinner walls (e.g. 500 mm) is indeed around the proverbial 1 metre, however in thicker walls rising damp can rise significantly higher. - Thicker walls evaporate more water into the living space. rising damp rising higher in thicker walls creates a larger evaporative surface, thus "dumping" more humidity into the living space. Several litres of evaporated water per day (= several hundreds of litres of water per year) is not uncommon - resulting in quickly filling dehumidifier buckets or significant condensation and mould problems.

- More water intake, more salts, more fabric damages: several hundreds of litres of water per year can draw up a significant amount of salts into the building fabric, explaining the severe plaster damage in some cases.

Past Historical References

The rising damp phenomenon has been consistently documents for almost 200 years. Written historical records are available in forms of various period publications and books.

1. Period Architectural References from the 1800s

The amount of independent, third-party information about the existence of rising damp is really staggering, the phenomenon being well-documented since the 1840s. Many architectural and professional books have described the problem, also advising about various solutions on how to overcome it.

Click on any of the titles below to expand more content.

The first known written historical reference about rising damp goes back to ancient Rome. The Romans, being excellent engineers, that have built some masterpieces that lasted over 2000 years. Historic records show that they not only were aware of rising damp, but they have also devised efficient solutions to combat it.

Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius in his famous Ten Books on Architecture has described the type of plaster mix that should be applied on walls near ground level subject to ground moisture:

"I shall next explain how the polished finish is to be accomplished in places that are damp, in such a way that it can last without defects. First, in apartments which are level with the ground, apply a rendering coat of mortar, mixed with burnt brick instead of sand, to a height of about three feet above the floor, and then lay on the stucco so that those portions of it may not be injured by the dampness."

The Builder was a journal of architecture published between 1843 and 1966. Issues from year 2 (1844) mention dampness rising from the ground due to capillary attraction. As a solution, to prevent the ascent of moisture up the walls, it recommends the use of slate inside the walls.

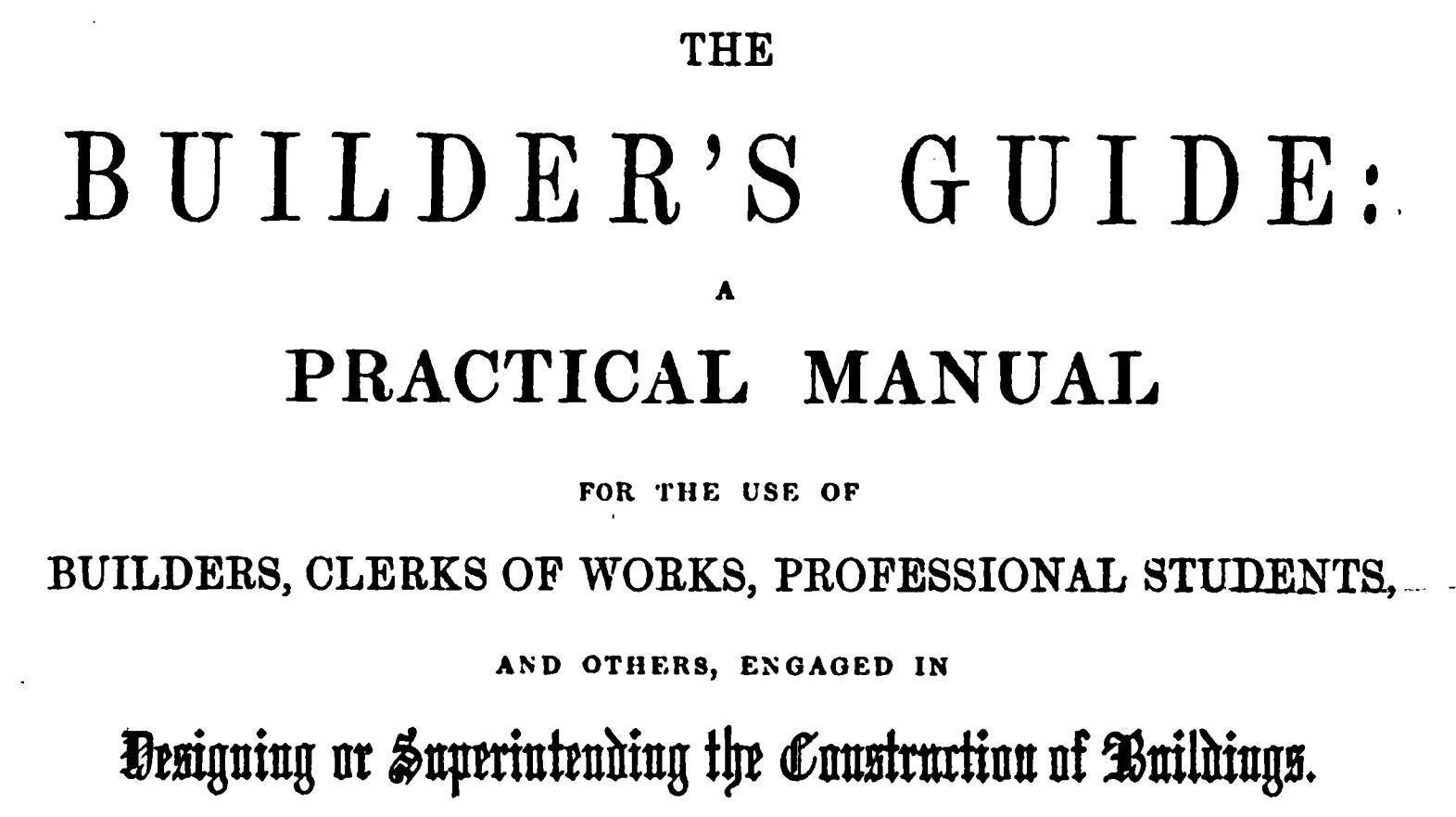

This professional textbook from 1851 is a practical manual written for architectural students, engineers, contractors and builders.

Dedicating a whole chapter to dampness, including to the prevention of rising damp, stressing the importance of separating the foundations from the rest of the wall with a damp proof course, to stop the upward migration of dampness.

"... to intercept entirely all communication between the foundation below and the walls above, no damp, as far as we have observed, can possibly find its way upward; and however damp the work below the asphalte (DPC) may become, that above will remain perfectly dry and unaffected."

French architects, independently, came to the same conclusion. Even if the footing of a building is always underwater (e.g. in a lake), using less than half an inch thick asphalt DPC keeps the walls completely dry.

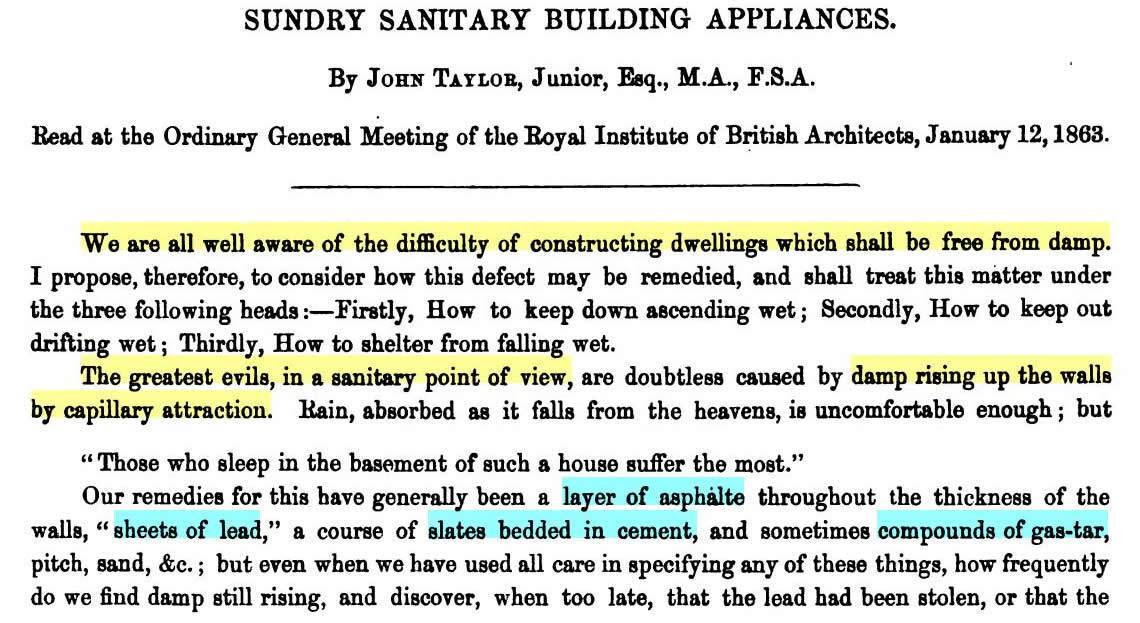

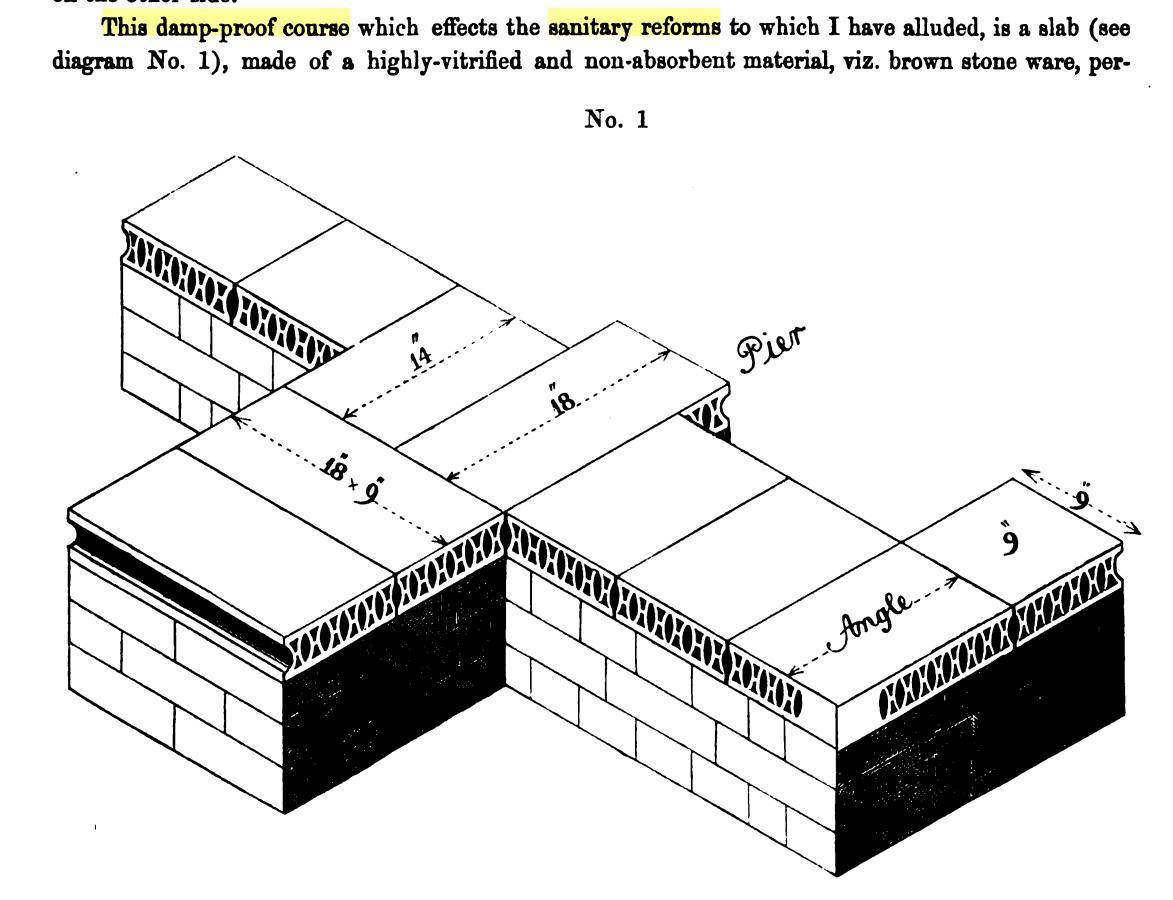

This paper read on 12 Jan 1863 at the General Meeting of the RIBA, discusses the sanitary aspects of rising damp in old buildings, and various damp proof course options as a natural remedy to the problem - about 20 years ahead of global UK sanitary reforms.

"The great evils, in a sanitary point of view, are doubtless caused by damp rising up the walls by capillary attraction. (...) Our remedies for this have generally been a layer of asphalte throughout the thickness of the walls, "sheets of lead", a course of slates bedded in cement, and sometimes compounds of gas-tar, pitch, sand etc."

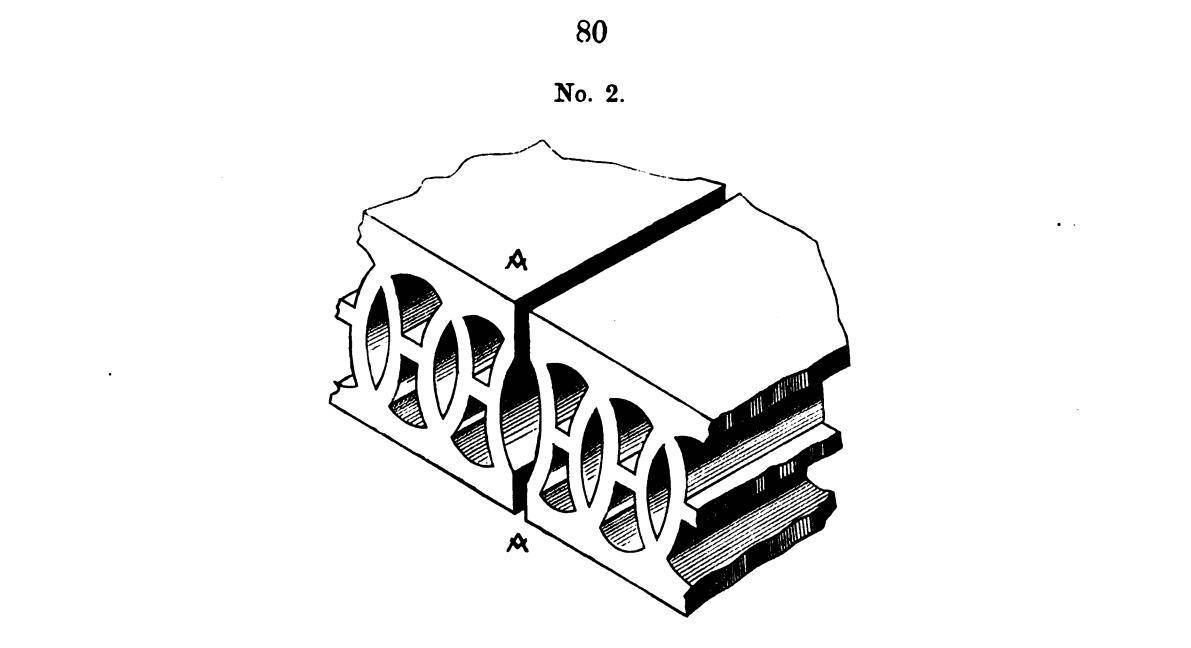

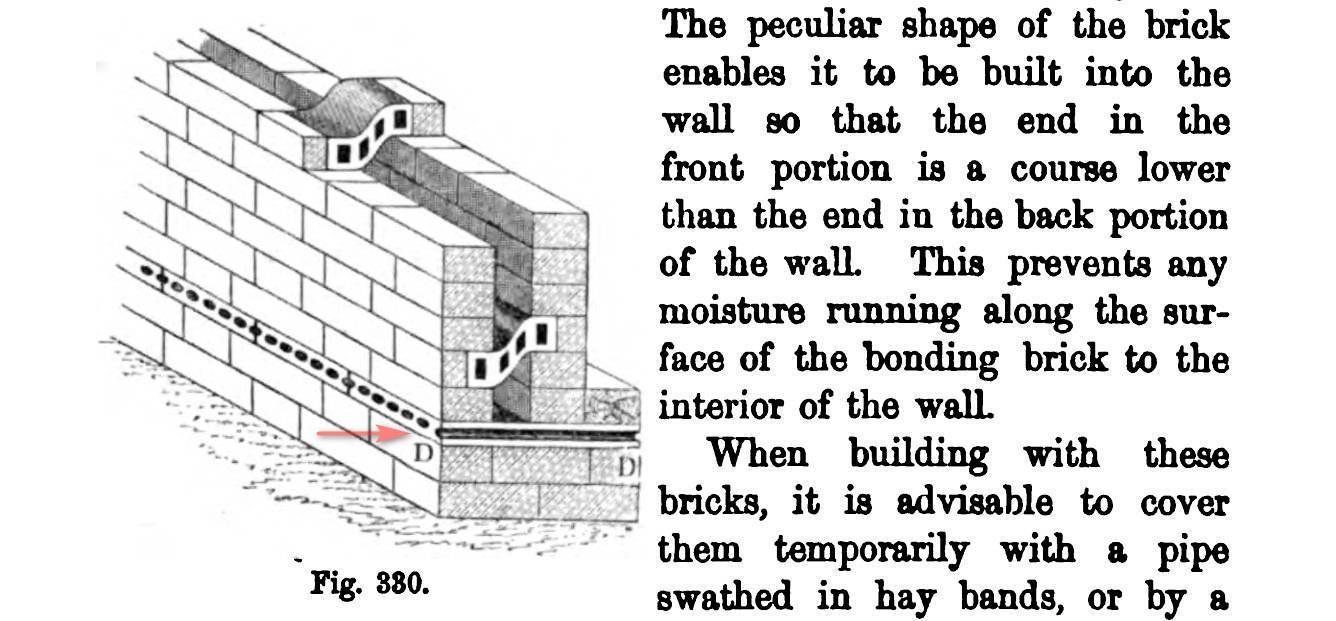

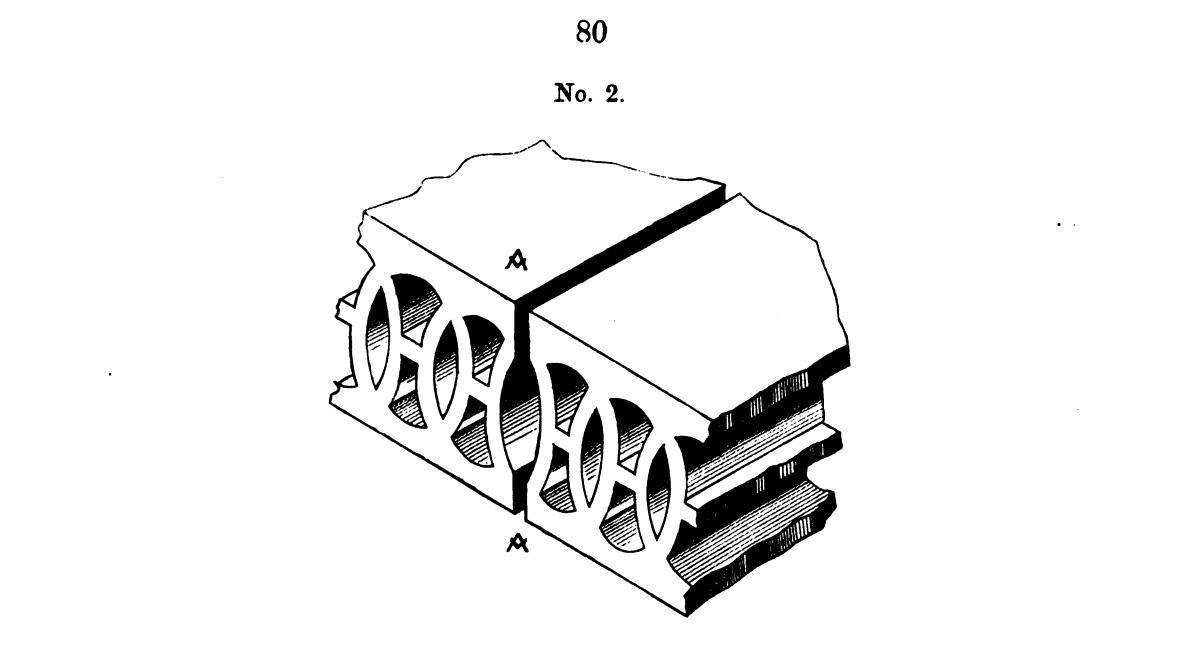

A new damp proof course is also presented to the attending architects - a layer of perforated bricks, laid as a row of ordinary bricks, to prevent the rise of moisture, while also improving underfloor ventilation.

Some of the architects' comments on this damp proof course technology included:

- Many new inventions are adopted with difficulty, including the idea of damp proof courses.

- Some concerns about their additional cost. Damp proof courses have often been skipped to save on material and labour costs.

- They should be better tested, although in buildings used (e.g. the great Artillery barracks at Colchester) they were very efficient.

- Their aesthetic look is a positive.

- Architects were in agreement that damp proof courses were the best method of keeping damp down.

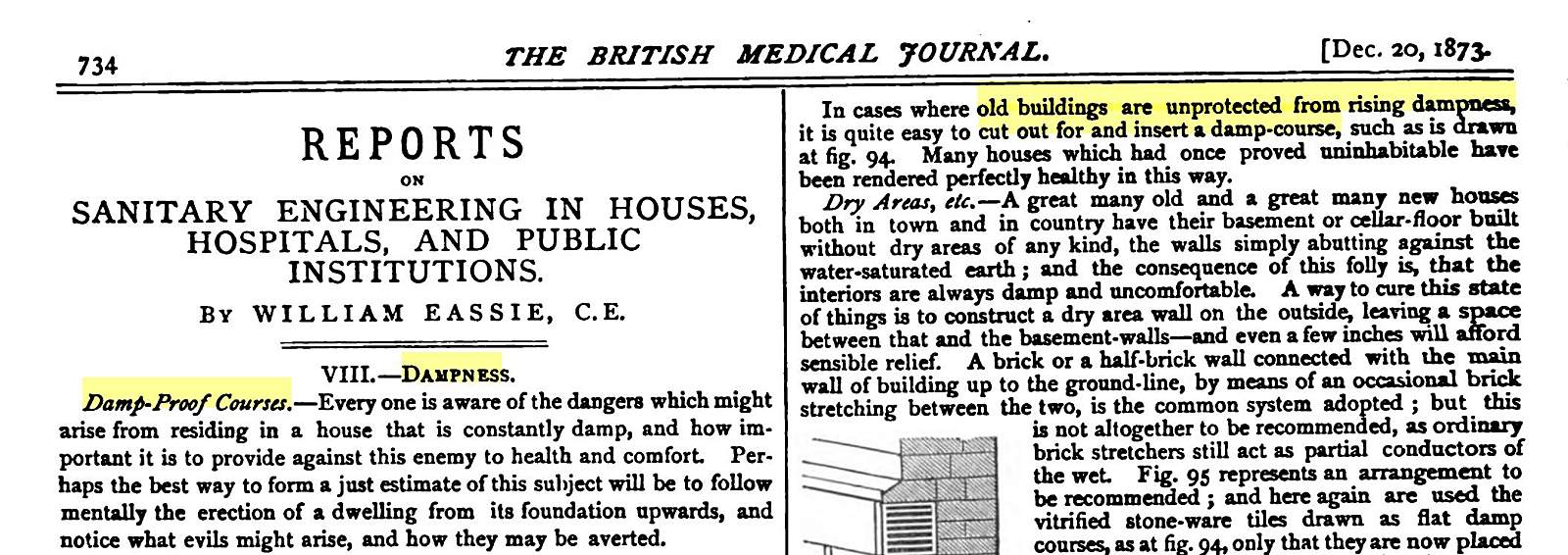

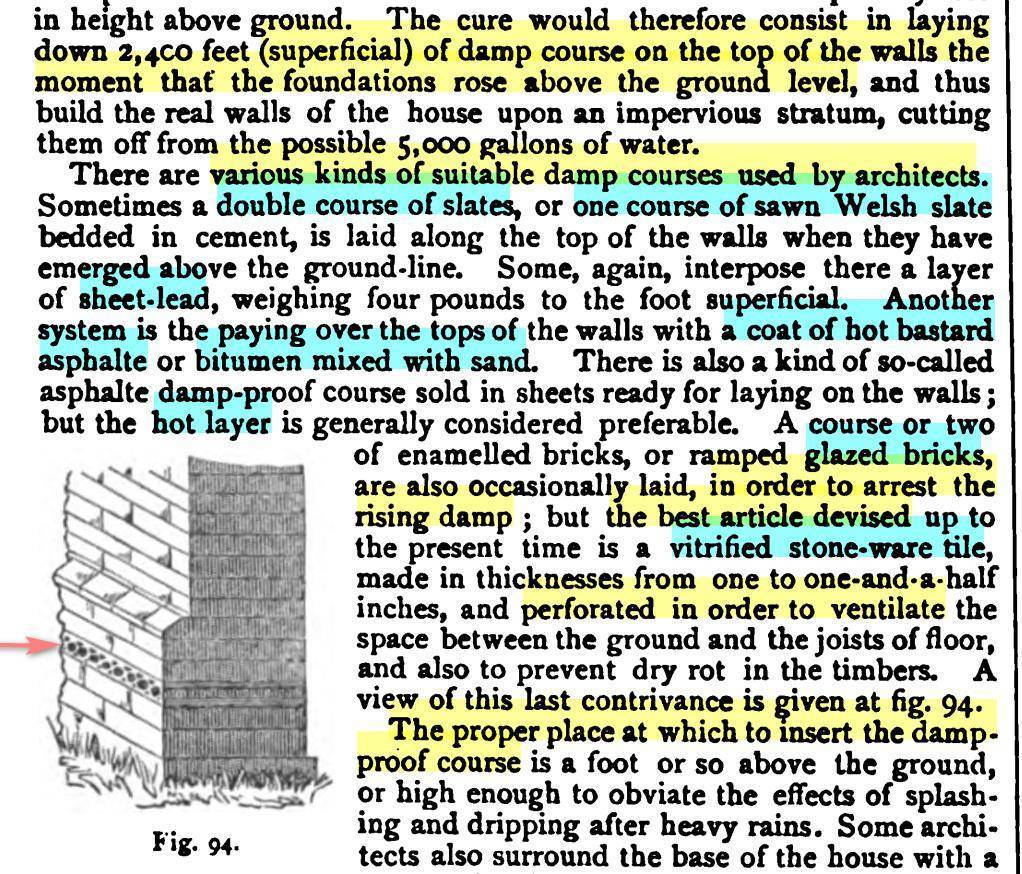

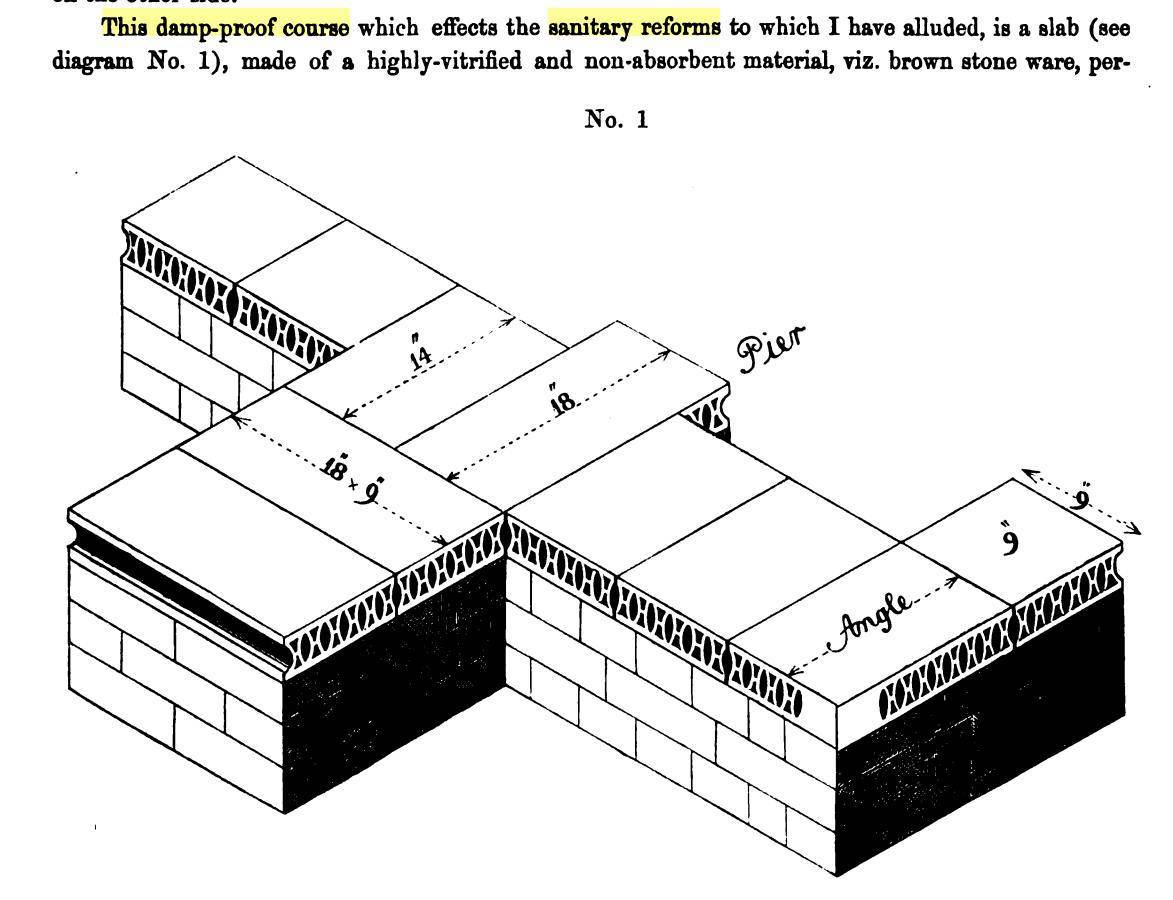

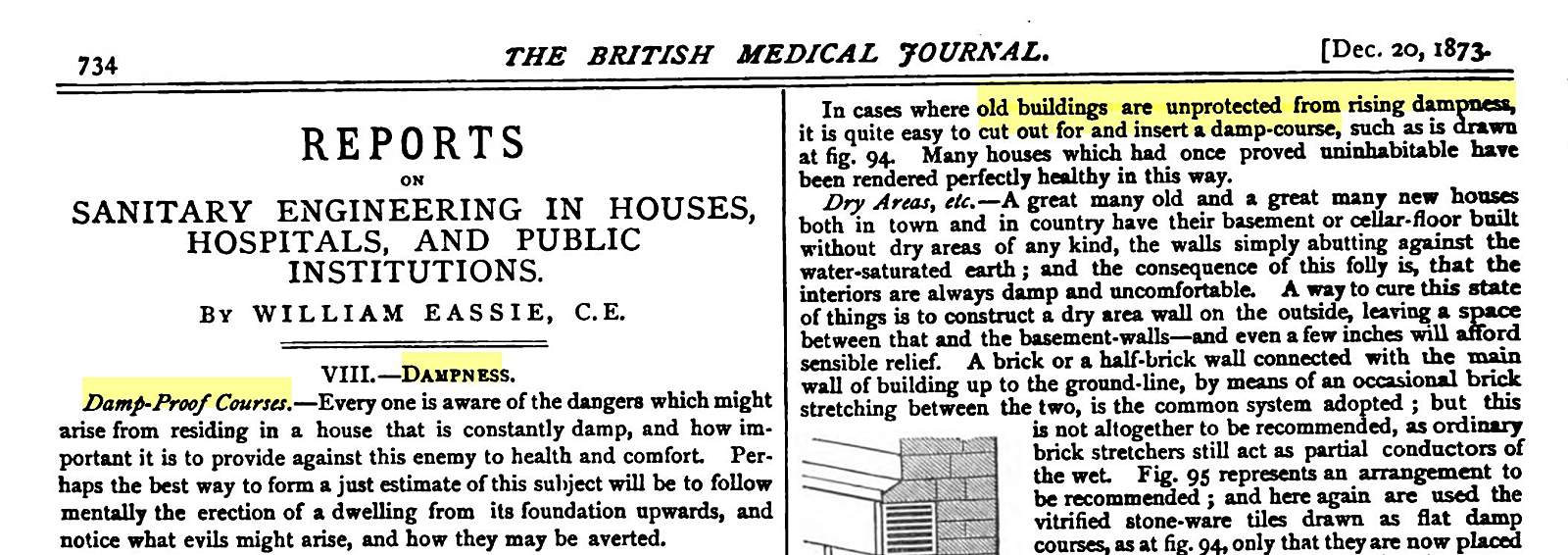

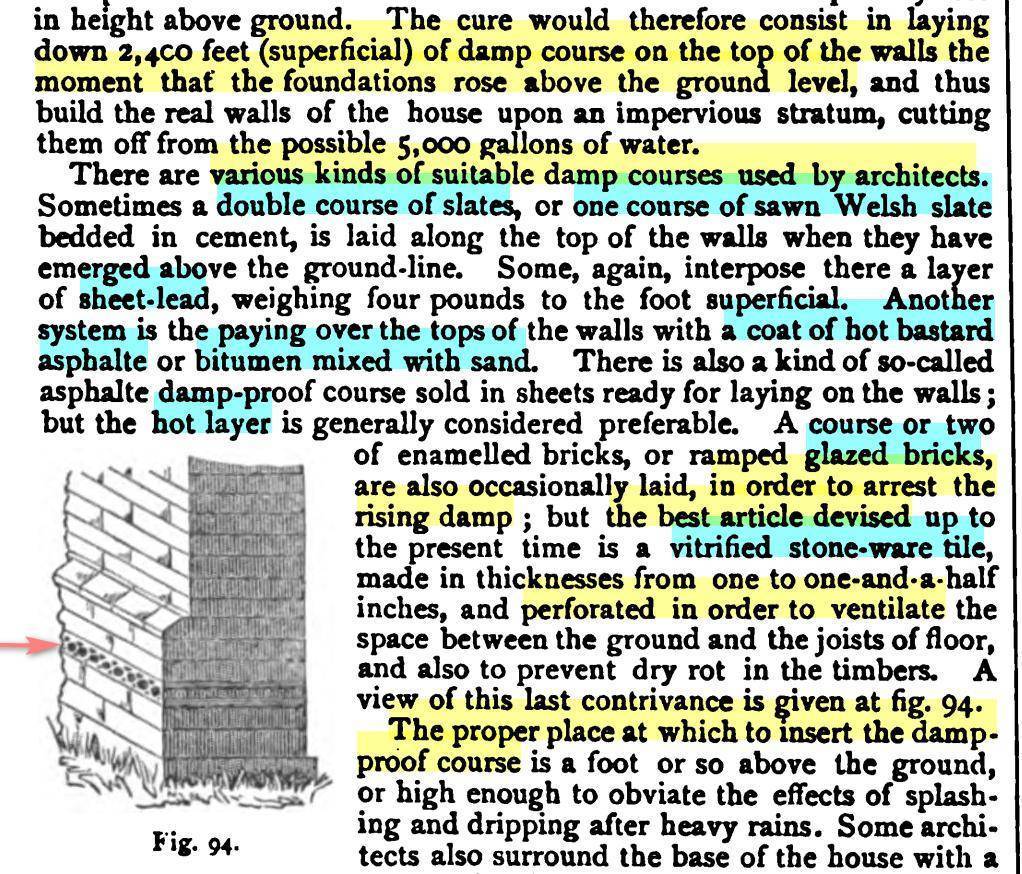

A report of the British Medical Journal dating 20 Dec 1873 discusses various sanitary aspects of rising dampness in houses, hospitals and public institutions.

Various damp proof course technologies used by architects are mentioned in the paper, including double course slates, Welsh slate bedded in cement, sheets of lead, hot asphalt DPCs, glazed bricks and vitrified stone-ware tiles.

The paper also advises the retrofitting of a damp proof course into old buildings, which turned uninhabitable buildings into perfectly healthy ones.

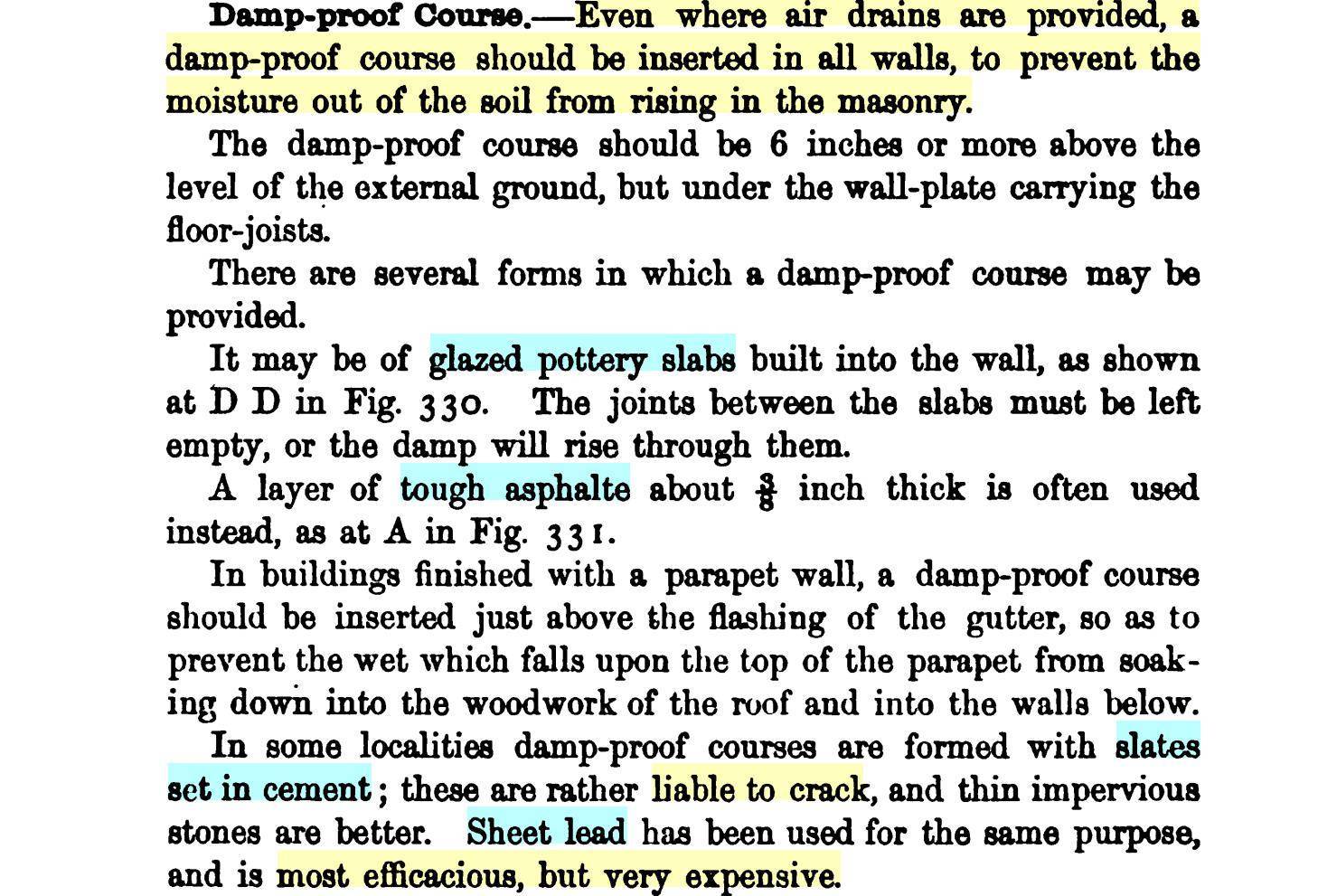

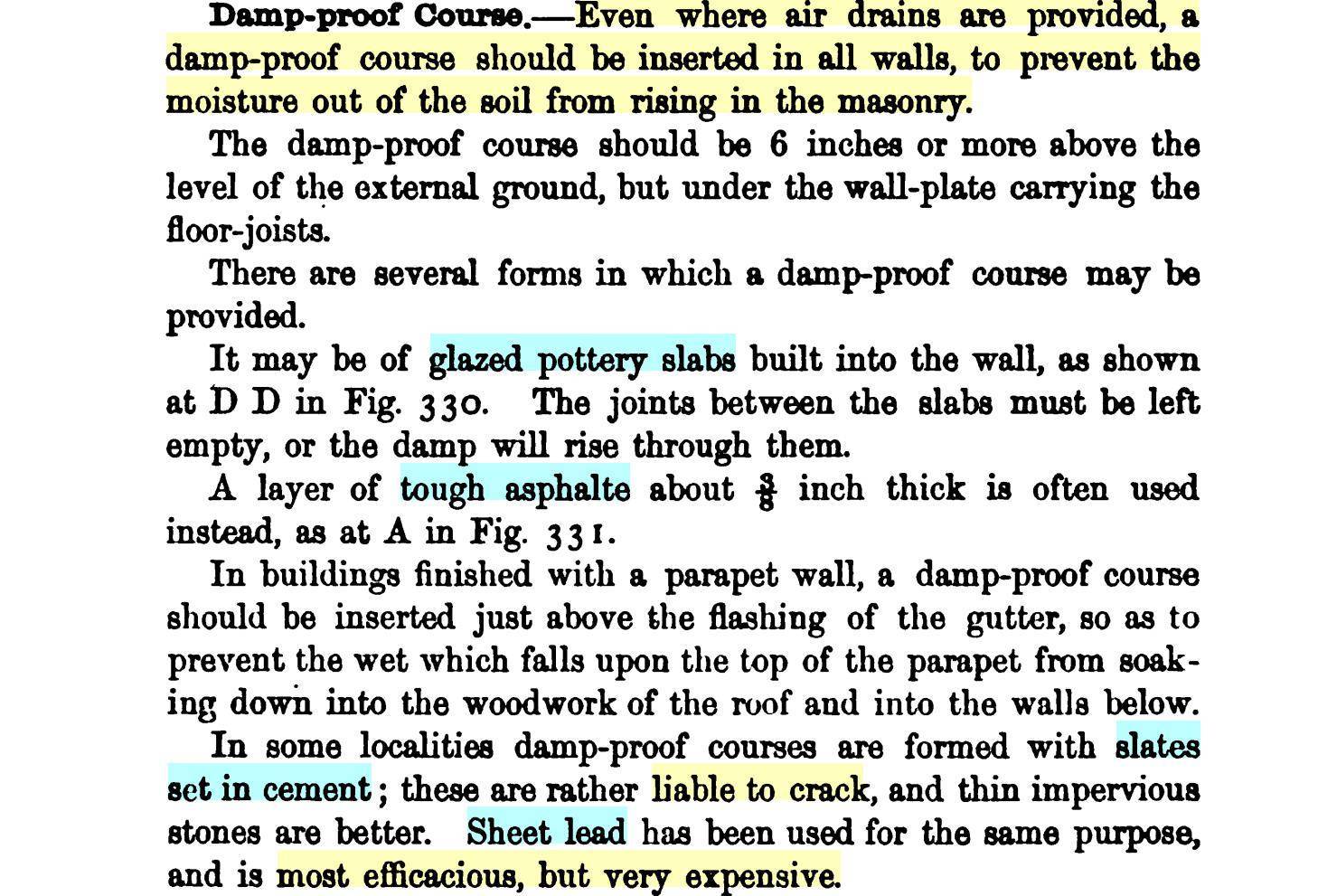

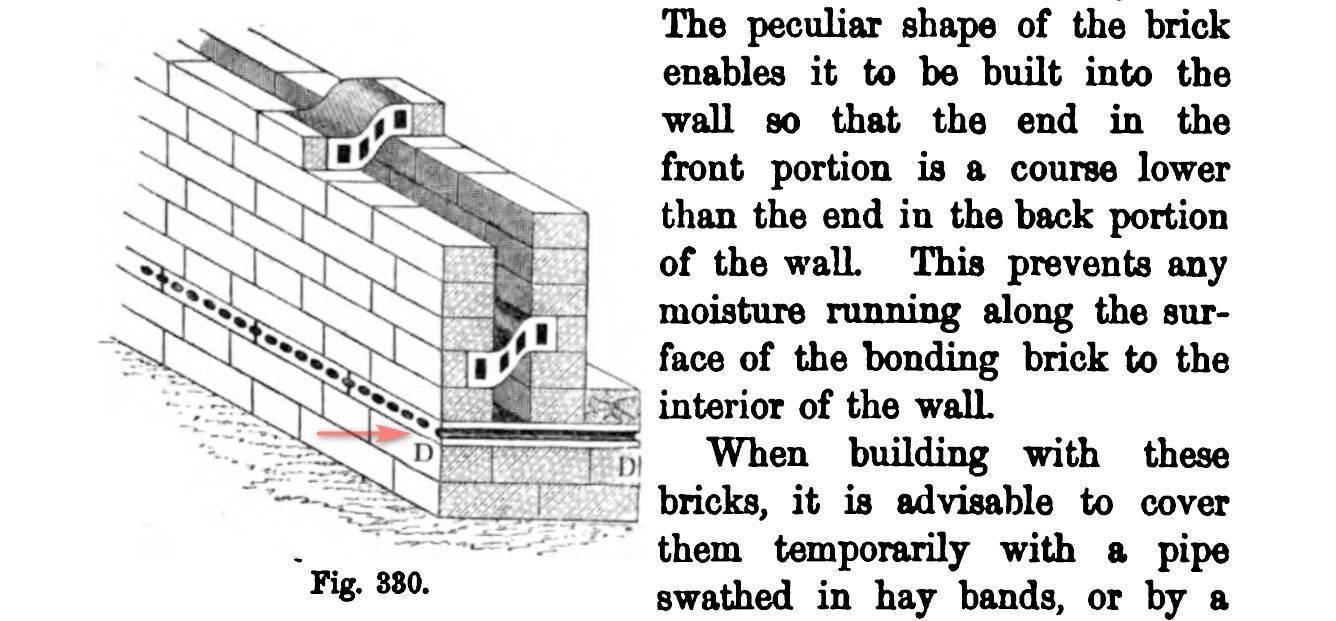

This 3-volume publication from 1876 was the official syllabus of a three-part advanced building construction course. A whole chapter is dedicated to the problem of dampness and how to efficiently overcome it, including rising damp, penetrating damp and falling damp from the roof or gutters.

Various damp proof course technologies are also discussed, making reference to the fact that slate DPCs embedded in cement are liable to crack and thus fail.

Glazed pottery slab damp proof course built into the wall:

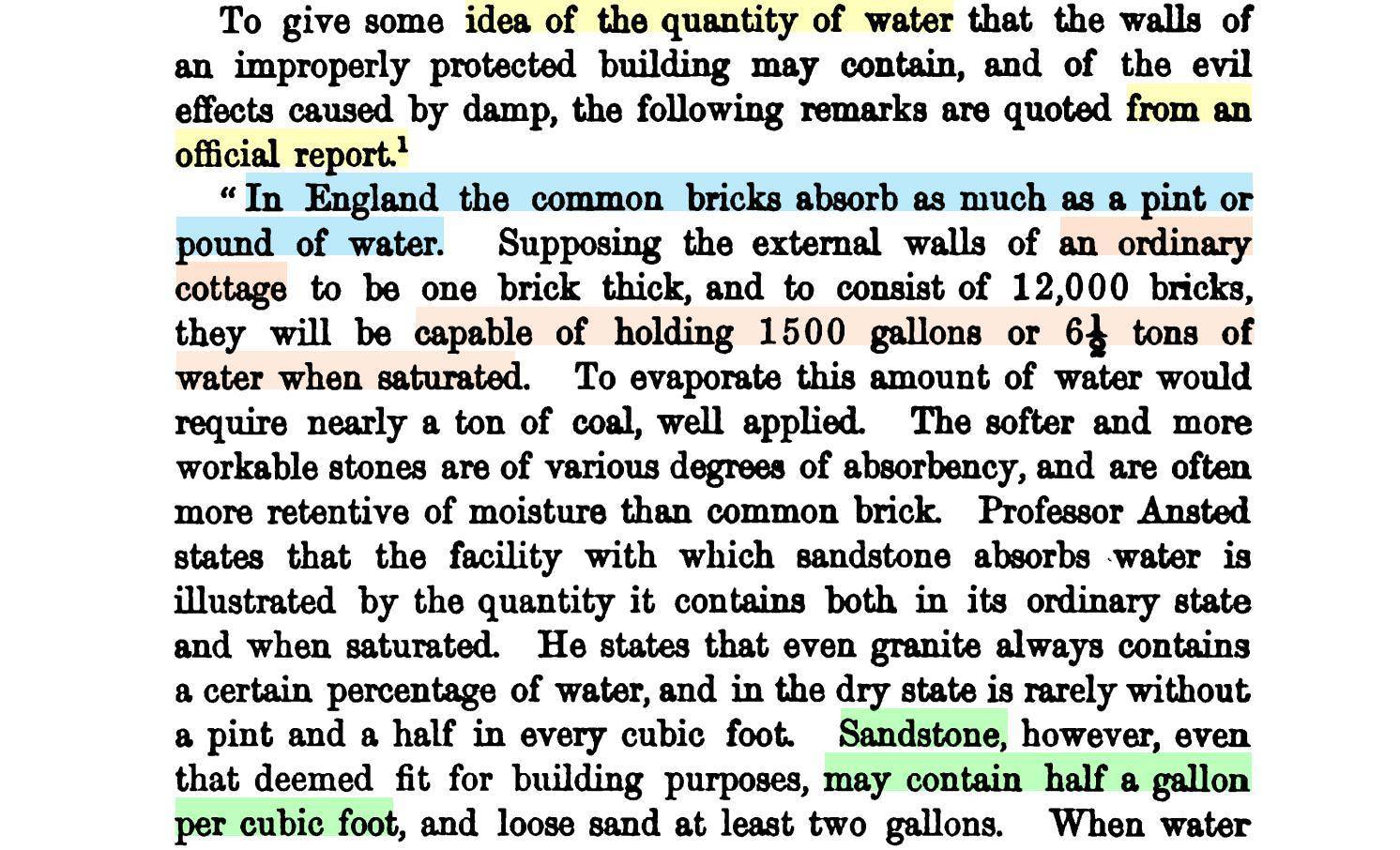

Lastly, according to an official report from the 1867 Paris Exhibition, some interesting technical facts from the book on how much water saturated brickwork can hold:

- In England, common bricks can absorb as much as a pint or pound of water

- An ordinary cottage consisting of 12,000 bricks, can hold about 6.5 tons of water when saturated

- Porous sandstone fit for building purposes may contain about half a gallon of water per cubic foot. (about 80 liters / m³)

Realizing the effect of damp walls onto the health and well-being of inhabitants, between the 1870s - 1890s a number of health bills have been passed throughout UK, all of them recommending damp proof courses as a means to combat capillary rising damp.

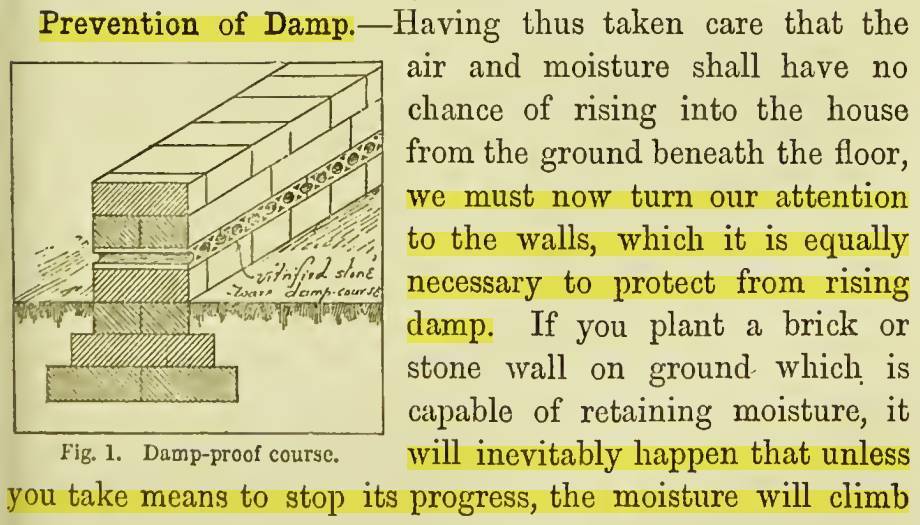

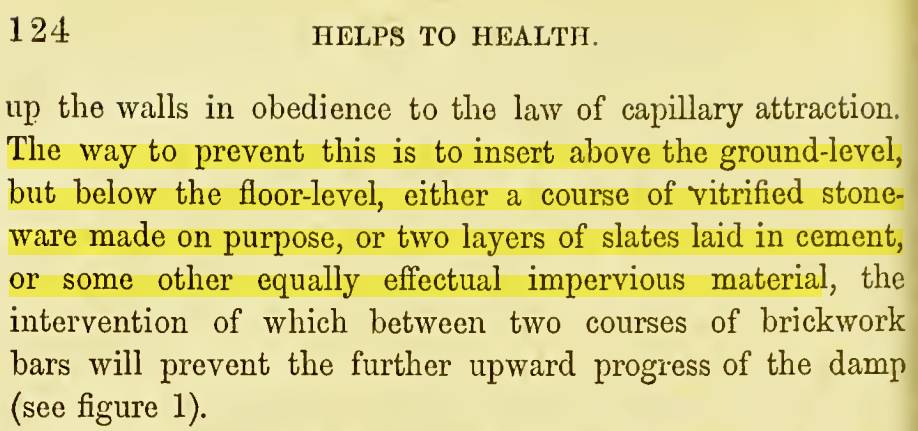

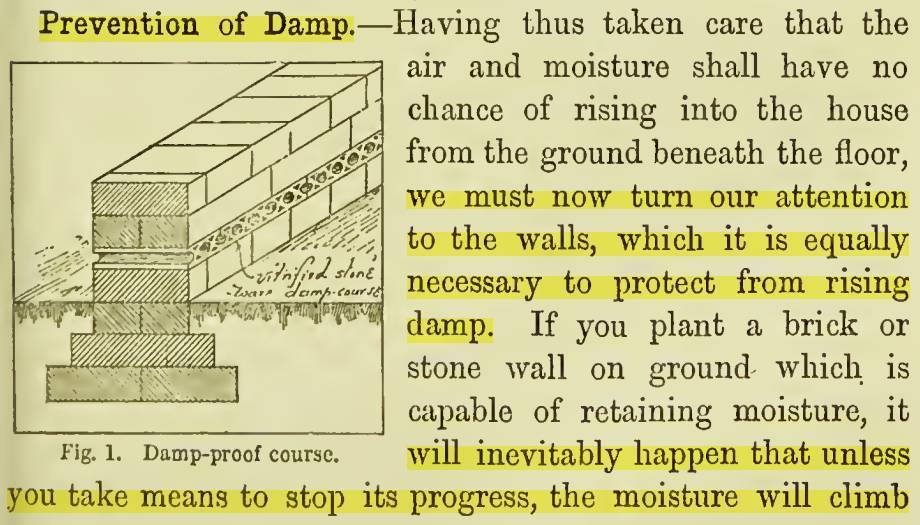

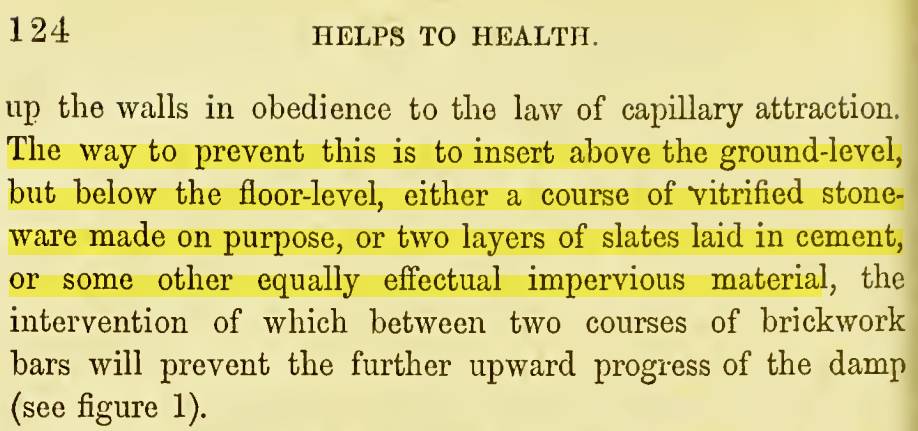

"We must now turn our attention to the walls, which is equally necessary to protect from rising damp. If you plant a brick or stone wall o ground which is capable of retaining moisture, it will inevitably happen that unless you take means to stop its progress, the moisture will climb up the walls in obedience to the law of capillary attraction."

Solution to the problem is a vitrified (glass-like) layer of bricks or two layers of slate.

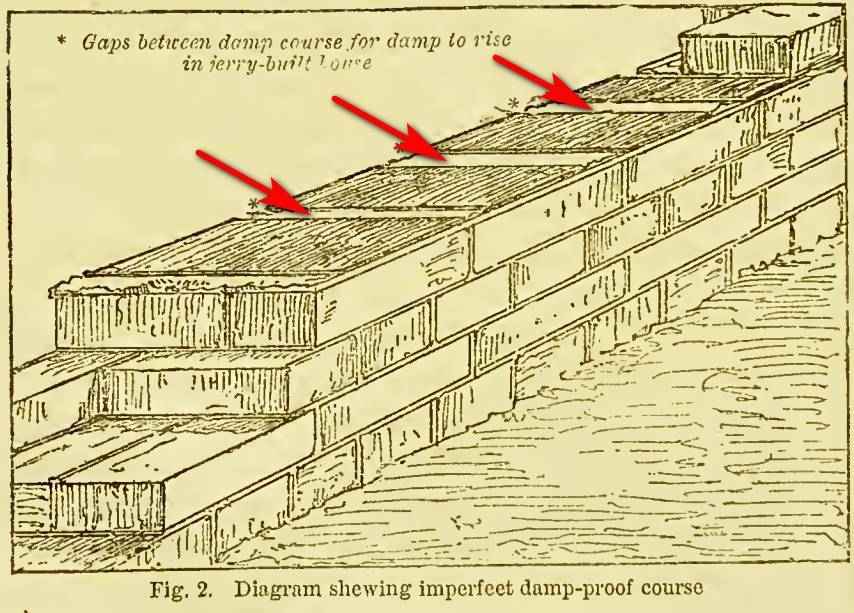

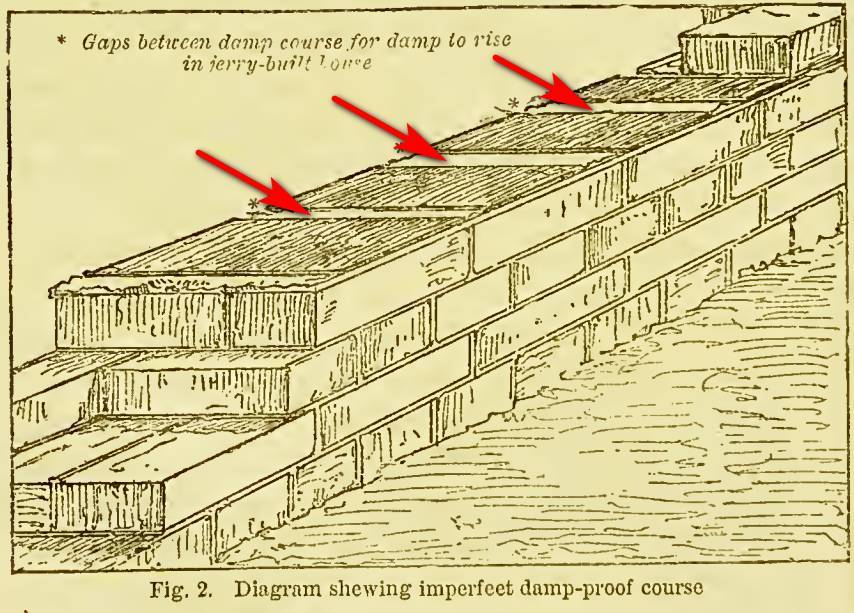

The book also provides technical advice with drawings, presenting the wrong way of laying a slate damp proof course, if gaps are left between them.

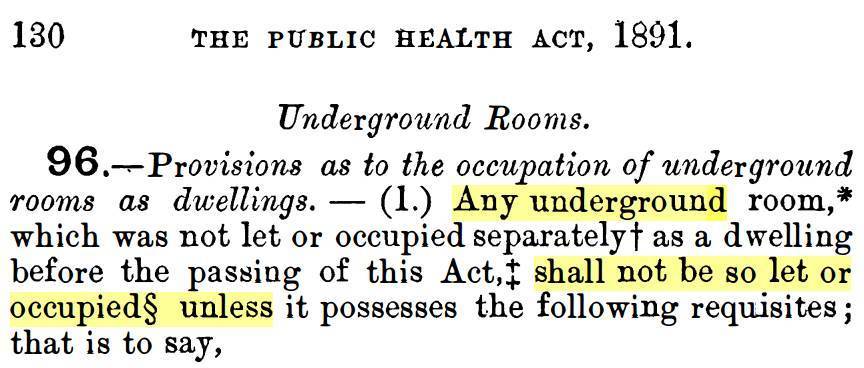

Clause 96 of the The London Public Health Act from 1891 stipulates the use of damp proof courses for underground rooms: "Any underground room (...) shall not be let or occupied unless (...) every wall of the room is constructed with a proper damp proof course."

2. Period British Books & Publications

Old books from the Victorian period have also documented that problems caused by rising damp, which were well-known in Victorian England, describing damages done to old 16th - 17th century cottages and country houses.

All these books are freely available from the Internet Archives as part of Google's old books digitization project. They can be freely viewed and downloaded as PDFs by anyone.

Click on the titles below to expand the references.

This American book published in 1851 discusses important aspects of house building in the United States: design, materials used, finishing, heating & ventilation etc. The problems of dampness is also addressed, highlighting the importance of damp courses (or the use of hydraulic mortars) to prevent dampness from rising.

The book also discusses in details most building materials used in the 19th century, highlighting that stone houses built without a damp proof course are more or less damp...

... and common lime mortar will not stop rising damp from the ground.

"The foundation of walls built of common lime mortar, will always be damp, from capillary attraction - common lime mortar offering no impediment to the absorption of the moisture from the soil, or to its gradual passage upwards into the main wall of the house."

This book published in 1870 presents 45 private residences of its time, focusing on practical aspects of house building, including: how to properly build walls, construct floors, roofing, ventilation, drainage, what materials to use etc.

The problem of dampness is also discussed in detail, with practical advice on how to prevent it, overcome it and build a dry, comfortable home. Rising damp must always be addressed by laying a damp course under every wall, whether internal or external.

"Damp course: a provision should always be made to prevent any damp rising up the walls from the foundations."

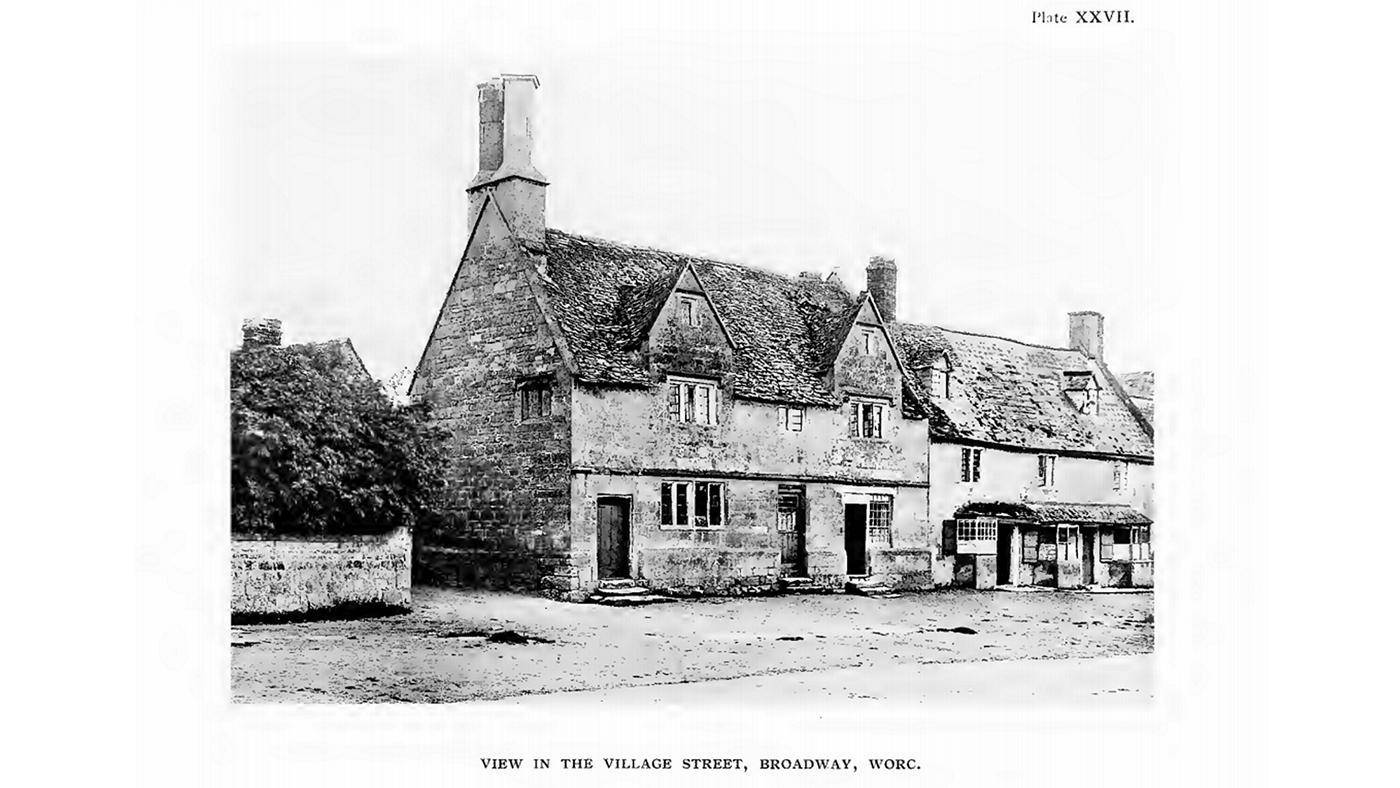

This book published in 1905, presents examples of typical domestic buildings, including some of the most noteworthy houses from Victorian England. The book highlights damages caused by rising damp in many old 17th century cottages - making some rooms almost unusable for living.

"... When the houses were built in sloping sites... by means of terraces and steps... these lower rooms, owing to wet and damp, are now almost unusable except at store places."

The reason why the ground floor rooms of many old cottages were wet and unhealthy, especially during winter time, was lack of damp proof courses, an unknown technology at the time when these cottages were built.

"The ground floor... laid directly on earth, with the result that the moisture readily soaked through, doubtless causing the rooms to be wet and unhealthy, and as damp proof courses were unknown when these houses were built, the lower part of the walls in winter time was moist and damp."

This book published in 1909 highlights the damp, disused condition of some rooms in old cottages due to lack of damp courses.

"Also the houses are often built on a slope, and the lower rooms are so damp that most of them are now disused. The stone floors, indeed, were laid direct on the ground, damp courses were unknown, so no wonder that the houses were not dry."

This book published in 1914, dealing with the restoration of old houses - weather cottage, farm house or small manor house - presents is detail the history, problems and restoration challenges of 40 old buildings stretching back 5 centuries.

Problems caused by rising damp are repeatedly highlighted, linking the problem and associated damages to lack of damp proof courses, unknown when these buildings were originally built. Several such examples are presented, and poor workmanship is also mentioned.

"Some people are apt to suppose that the buildings of historical periods were constructed on particularly sound lines. That, however is hardly the case. It is to the nineteenth century that we owe the use of such devices as damp-courses, and the lack of them in early buildings has not only shortened their lives, but many many of them uninhabitable, sometimes beyond redemption."

Some repairs followed the principles laid down by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, the SPAB, already in existence since 1877. The book praised the SPAB's rigorous work and conservative approach in retaining as much old building fabric as possible. At one building the repair works also included the insertion of a solid damp proof course while undertaking some foundation works.

"...the principles laid down by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. It is not only conservative in the preservation of every scrap of old work, but eminentlv satisfactory in appearance. For the needful repairs to the walls bricks were made locally of the same size as the old ones. The attitude of the S.P.A.B., familiarly known as the Anti-Scrape, is sometimes more rigorous in respect of the alteration of old buildings than some antiquaries can endorse. Its work has been of immense value, however, in forming public taste and in checking the vandalism which raged unhindered before the Society was formed."

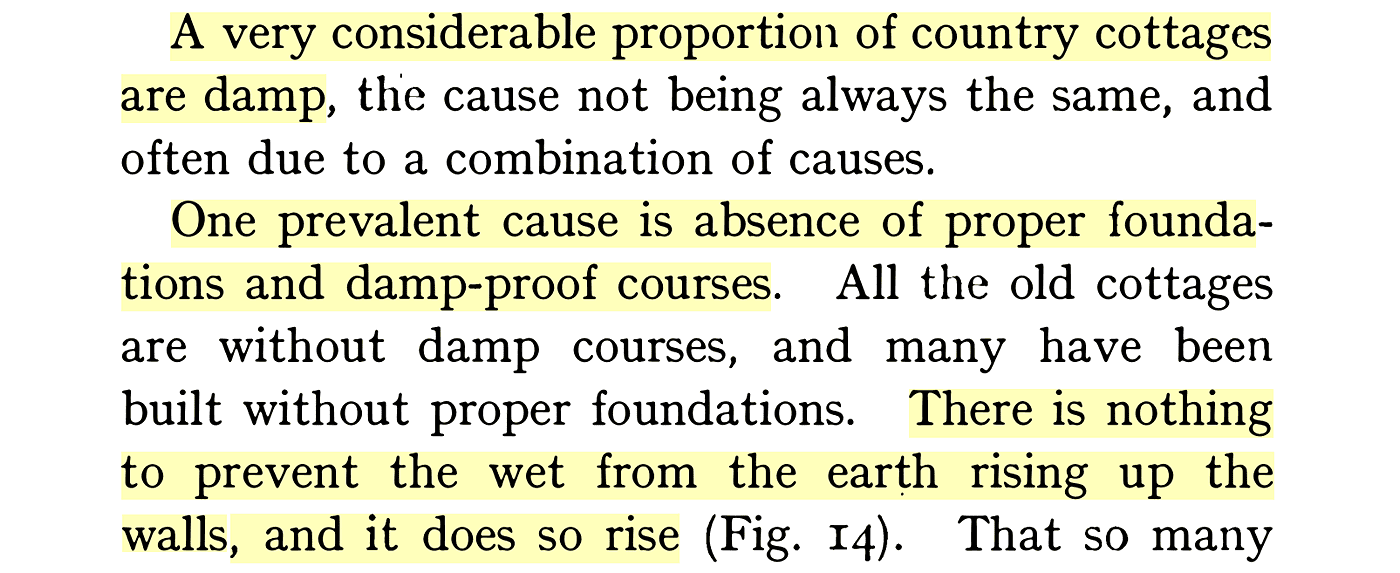

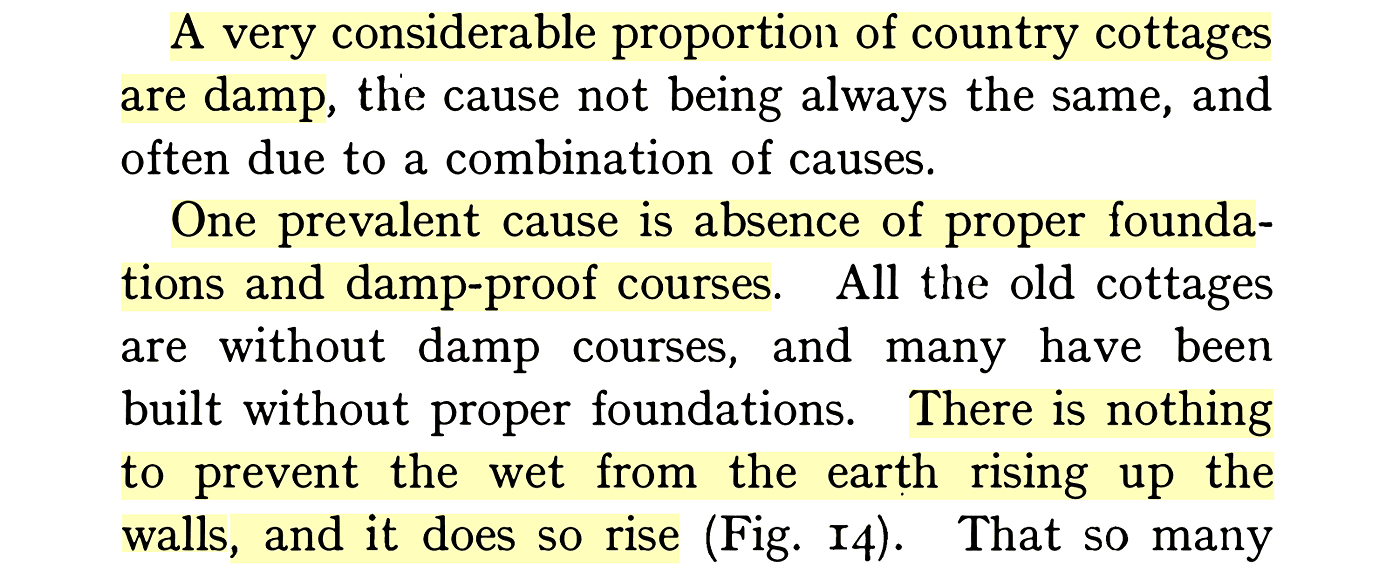

This book published in 1915, written by the Medical Officer of Somerset County, discusses important aspects of rural housing, including: the housing shortage, housing conditions, health and sanitary problems etc. The effect of various types of dampness are discussed in detail, based on the findings of professional surveyors.

"A very considerable proportion of country cottages are damp... due to a combination causes. One prevalent cause is the absence of proper foundations and damp-proof courses. There is nothing to prevent the wet from the earth rising up the walls, and it does so rise."

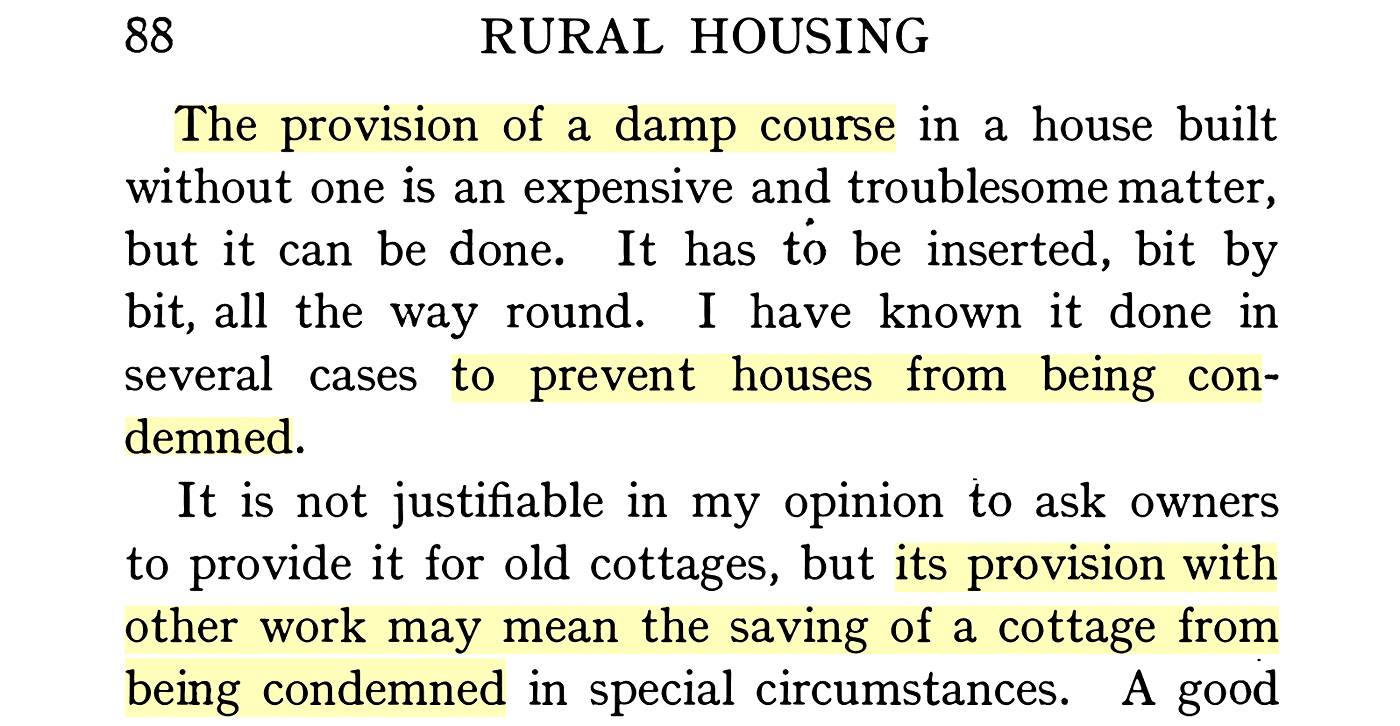

Rising Damp is listed as a major problem that can be remedied with difficulty. The solution is fitting a solid DPC while other works are being undertaken. Failing to do so, the lack of a damp proof course, often makes old buildings uninhabitable, also resulting in their long-term decay.

"The provision of a damp course... is an expensive and troublesome matter. It has to be inserted... to prevent houses from being condemned." (Def: condemned: officially classed unfit for living)

On the next page we are going to explore in depth the other viewpoint of why rising damp would not exist.